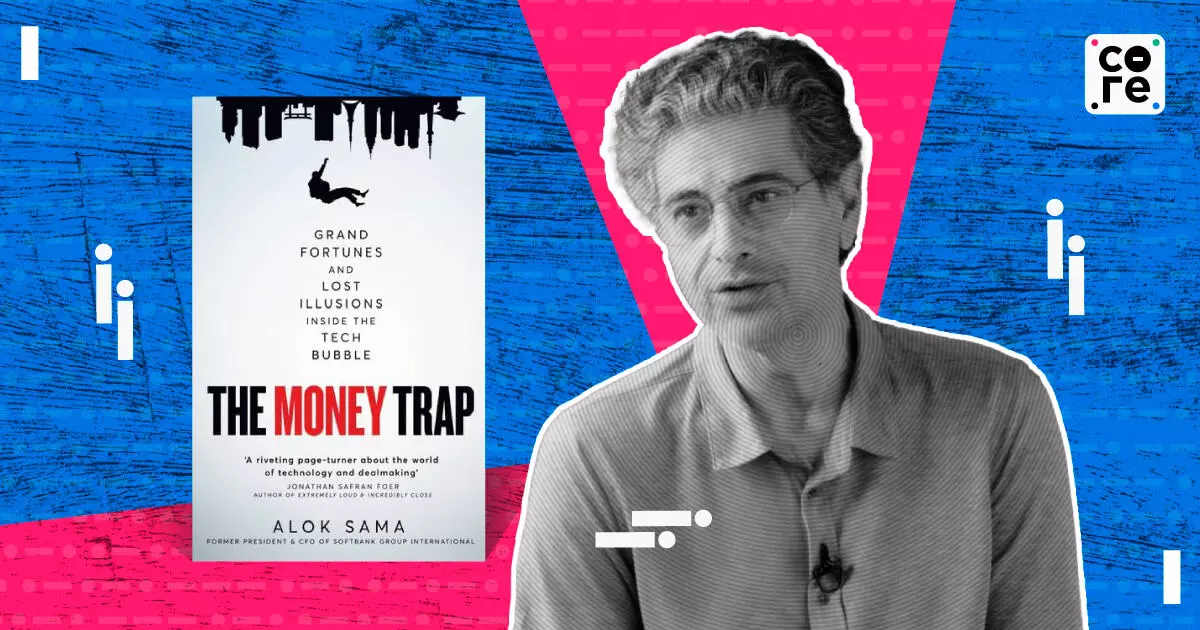

Ex-SoftBank President Alok Sama On Masayoshi Son, Bold Investments, And Writing His Book

In this week’s The Core Report's Business Books Sama spoke about his transition from a successful career in finance to becoming an author, and what he learnt along the way.

NOTE: This is a transcript of the interview including questions by the host and responses by the interviewee. Human eyes have gone through the script but there might still be errors in some of the text, so please refer to the audio in case you need to clarify any part. If you want to get in touch regards any feedback, you can drop us a message on feedback@thecore.in.

Hi and welcome to The Core Report's Business Books edition. So the Business Books edition is a new series that we're starting which is essentially conversations with authors of business books where we try and bring out two slightly different things. One is of course what you can take away from a business life point of view, that's your own life and approach to work and workplace.

And the second is more strategy in business and what you can apply to maybe grow your business or expand it or do the right thing. My guest for today is Alok Sama, the former president and CFO of SoftBank International, who you may have heard of and that's where it'll get interesting very soon. SoftBank has been founded by and run by Masayoshi Son, the famous venture capitalist who also has invested extensively in India.

Alok Sama has worked in many regions, he used to be a senior managing director at Morgan Stanley and has written this book, it's called The Money Trap, Lost Illusions Inside the Tech Bubble. Alok, thank you so much for joining me. So tell us about the name of the book and why you chose that.

It was one of many names I batted around with my publisher and it wasn't my first choice, I went along with it because it rhymes with honey trap in the book, if you read it there's actual honey trap in the tenth and sexual blackmail. So there's a play on that but the reason wasn't necessarily my first choice, it's a little bit cliched but what it refers to obviously, which I think most people get is money being a trap or the pursuit of money being a trap and most of my colleagues, particularly those who've been in the business for a while, Wall Street or technology investing or whatever, they kind of get it, they instantly know what that means because a lot of them are still in it. So and why is it a trap? It's the allure of money, it's the oldest thing in the world.

I mean, when you're caught up in the pursuit of money and it keeps going, it's just very easy to break free of that. I mean, there's always something more you can buy, right? I mean, there's always a bigger play in a bigger home and I repeat that many times in this book, always something more and that's not ideally the way it's supposed to work.

I think our old Vedic philosophy understood this and I think there's some very meaningful wisdom in the notion that there's stages in life and at some point you really got to let go.

And you arrive there because you experienced it, satiated yourself and hit some kind of ceiling?

That once again is too cliché, nobody does that and I don't consider myself one of those like the monk who gave up the Ferrari. I think that's a, without putting down anyone, I think that's a bunch of BS. For me, it was a case of being in a position where it just no longer made sense.

We talked a lot about what I went through in my days at SoftBank or at Morgan Stanley and there were all situations in which my position wasn't a happy place to be in. So, there was a natural break point but absent that, I mean, it's quite likely I'd be as strapped as a lot of my former colleagues in that money trap.

So, I'm going to come to the book in a moment. But the word trap again, I mean, just to spend a few more moments on that, you're saying that it's something that... except in post, if that's what you mean.

Nobody's holding a gun to your head saying you're going to stay in there.

That's why it's interesting to write about.

And in your case too, I mean, would you have left it had things not reached that point where you had to, let's say, leave that fund and you had to take another position. There was this whole campaign, smear campaign that was going on.

I think it's a better than even chance, likely even, that I would not have left and that's exactly my point. I mean, it's, I don't want to pretend to be, hey, I'm moving, I'm taking sannyas or whatever. I mean, it was very much a case of being in a situation where you've got this bizarre thing going on, which is enormously stressful.

And it's very clear that from a kind of so-and-so who I admire tremendously, still do, was kind of a bit of a different path from what I wanted to do or was focused on. It just made sense to part ways.

And in the book, I don't know how many secrets that you've revealed that you should not have revealed, but clearly you've revealed some and many of them reflect obviously your proximity to Masayoshi Son of Softbank or Nikesh, who was earlier in Google and then went to Palo Alto Networks. So what made you write this? I don't know, is it a tell-all, is it tell somewhat or tell a little bit?

Well, I don't believe I've revealed any sequence. I was very careful about that and I want to be very honest about that. Anyone who is buying this book or reading this book in the expectation that I'm going to spill the beans is probably going to be disappointed.

Candidly, the appeal of this book and I'm overwhelmed by the reception is much more in the style of writing and my observations on events that are generally facts that are publicly known. When you leave a position such as mine, you always sign an NDA. I think most people appreciate that.

Clearly, I don't want to be on the wrong side of that. So clearly, I've made an effort. I was very aware of not revealing anything that could be passed through this confidential information.

So I don't know if that answers your question, but from my perspective, there was always an awareness.

And yet you do bring out personality facets including of Masayoshi Son.

The complexity of the individuals, absolutely. I mean, that to me, as a writing project, that's kind of what you focus on, which is not kind of positioning people as good or bad, not binary, that's very simplistic, is to bring out their complexity, what I admire them for, what people admire them for, and not necessarily talking about it in that fashion, but just observing and describing their actions and their behaviour and let the reader judge for himself or herself what they make of this individual.

So did you take up writing as a more formal project, including training yourself for it because you wanted to write this book or was the book the outcome of that?

No, it's a good question, the latter, very much the latter. I wanted to be, it's been a closet ambition for the longest time. I figured that the best way to pursue it, it was one of those like it's already late, but it's not too late.

And so I entered a graduate programme at NYU, full-time MFA degree, which is quite demanding and a terrific experience. And as one does in an academic environment, in a student environment, I experimented a lot. I wrote all kinds of stories.

And what resonated with people is I do have what people might describe as a rightly eye for observation. I mean, just coming into your studio or walking around, this is a really interesting neighbourhood, right? And I'm just throwing away pieces of information that at some point, maybe tonight if I have time, I probably won't.

I'd love to, I don't have a diary, but I keep writing about things that I see. And that's something that I've always wanted to do, to be a writer, I mean. And as I experimented in college, kind of bringing out kind of with a rightly eye for observation, some of the things, some of the situations I've been in, whether it's flying private or doing, you know, $50 billion deals, those are not situations one associates with aspiring authors and novelists.

So just made for an interesting, and when I managed to kind of, when I started to focus on that five-year slice of life, which is what this book is focused on, I managed to string that together as a narrative. That's kind of how this book was born.

And does it have the kind of detail it has, for example, your meetings and who was sitting where and what wine was served, and so on, because you took notes later, or is it something that you recorded during the process of writing?

A little bit of both, you know, keep in mind that some of the situations on Sanjh's dining room or plane that I'm describing are situations, locations, scenes I've been in on multiple occasions.

Like Tokyo, Conrad.

Exactly, the Conrad Hotel or the, you know, the double-height reception room where the piano is and, you know, how people behave.

The missing floor.

Yeah, the missing floor, exactly, you know, and Amasa's dining room, over a hundred times. So it is, that stuff is relatively easy. Some of it, you know, you kind of jog your memory, you talk to people who are there with you, you ask them if they remember, mostly they don't, because this is already, some of it is already 10 years old.

And, you know, you kind of string it together and tell the story in a coherent way. But the idea is, you always want those details, because you want the reader to feel that they're in the room. And that's a lot of the positive feedback I've had on the book, which is people feel as if they're in the room.

Yeah, and sampling the wine, which I'm sure they can't afford.

Tasting, sampling, in some cases smelling, observing. Yeah, I mean, that's the, you know, as a writer, that's what you aspire to create.

Yeah, so tell us about Masayoshi Son, to someone who doesn't know much about him, or actually, let's assume he or she doesn't know anything about him, except that it sounds like someone who's big in the world of finance.

Yeah, the way he describes himself is probably the best way to understand him. He calls himself the crazy guy who lives in the future, or crazy guy who bets on the future. So he's a futurist in that term, futurist visionary.

It's used a little bit usefully in the Indian context. I don't know how many people you'd put in that category, maybe Dhirubhai Ambani. I mean, there's only a handful of people.

And they come along once every few decades, literally. So he's one of those people. He's iconic in that way.

And he's proven that time and time again, foreseeing the smartphone revolution, the internet disruption, and now AI, embedding big time monumentally by any standards on those disruptive changes in technology. So that's the most important characteristic. On a more personal basis, I found him to be charming, engaging, funny.

We had a lot of fun together, a lot of laughs with him. The other more business characteristic, actually, maybe that should have come second. A lot of visionaries, you think that big picture people don't focus on the detail.

His focus as an operator on operating details can be microscopic. If there's a, I described this incident where there's a defect, a blind spot in Sprint, and Sprint was a phone company in the US that SoftBank owned, that there's a blind spot there, he will work with his engineers, identify it, go tell the Sprint people to fix it. That degree of focus is very unusual to see.

When you say blind spot, you mean somewhere where there's no coverage, there's no coverage, there's no signal, right? So that kind of focus is rare. Or you don't normally associate that with people who you kind of think of as big picture visionaries.

That's very unusual.

Because he was also an inventor and a technologist.

Yes, yeah, he has. I haven't got back and fact check this, but if I'm not mistaken, used to be, I think the number was 350 patterns, and it's probably more by now. But yes, I mean, he's a technologist in the true sense.

Now, one of the things that distinguished him is obviously his ability to take mega bets. You know, there's, I mean, they were, when everyone else is talking about millions, he's talking billions, and they're talking billions, he's talking about hundreds. How do you, coming from where you do, including in investment banking, how do you adjust yourself to that level of thinking?

No, that's a great question. And, you know, lots of times people ask me, why don't you hold him back? Or, you know, because he, let's be fair.

The flip side of it is, if you look at Son San's history in investing, there was, to say the least, two major hiccups. One is he went too far in the year 2000, and documented in the Guinness Book of World Records, lost the most money ever, right? World record.

And then again, I don't think his personal network declined by quite that much, but 2021 was a major, major setback for him, right? So he has gone too far, and he's publicly recognised, not even recognised, he's self-flagellated himself for doing that, particularly the second time when he made some, you know, kind of fairly strident kind of public proclamations about how ashamed he was of having made these mistakes. So, he has done that.

But the flip side of it is, on the big stuff, he's been spectacularly right. It's a long-winded way of answering your question. You know, very often when people ask me that question, my response is, well, you know, if I'd held him back, or if he'd listened to people like me, he probably wouldn't have done Alibaba.

Arm is a deal I'm very closely associated with it. I mean, I was on the director by side, setting management compositions, setting strategy, etc. Great, but I would not have had the courage to buy Arm, because putting on my kind of nerdy banker hat on, analytical hat on, I would have said, look, I mean, it's already expensive, we're paying a control premium, I'm not convinced.

And he never had any doubts. Look at what he's accomplished. It's a $100 billion market gain.

It's quite remarkable.

Now, what I would wonder from outside, perhaps you also did, and you, I think, alluded to it in the book, this is the same person who invested in Arm, which obviously turned out right in hindsight as well, and also invested in OYO, which was obviously something dramatic from your perspective, and so was it from the perspective of someone like Sequoia. So, my question really is, how do those two things converge, even as a process of thinking? So, from outside I'm saying, okay, is there a method to this person's madness?

Now, this doesn't seem to suggest method, or is there?

Well, let me put it this way, there isn't a method that you can copy. Like a lot of people ask me, what can you learn from it? You can learn a lot from Son San.

Probably the number one takeaway for people out there is resilience. I mean, just think about, there's this Icarus flying close to the sun metaphor, everyone's familiar with that. Close to the sun, crashes, kind of flies again, crashes and flying again, higher than ever.

That's remarkable resilience. So, that's one thing, life lesson, not just technology investing, we can all run, but you can't emulate someone like a Masa Song or a Steve Jobs, and there's an element of creative genius that just simply cannot be taught. Even as an investing method, there is a Warren Buffett way, there is a Sequoia way, not to put down Sequoia, there's some fantastic, look at that crack record, I mean, it's remarkable, there's some terrific technologists, but there is a method to their madness.

I mean, they go about it in a traditional way, and if you're a young associate, it's an apprenticeship model, and if you're working alongside some of their great partners, you learn to think about things like, basic things like, not to suggest so-and-so doesn't, but you look at kind of size of the market, addressable market, product market fit, entrepreneur, track record, is he dealt with failure, resilience, all those characteristics.

You structure a deal in a certain way with type governance, you drip feed capital based on achieving certain benchmarks, and you progress from one round to the other round. I mean, there's a method that's worked for them, and they know that of any 10 deals, like one might be a home run, and they're kind of going to be a bunch of duds, and there's a method based on experience, in terms of where you focus your resources. I mean, so that's Son San's approach is very different.

I say that in the book, that he looked at founders the way they want to be looked at a founder. So he will, you give the example of his approach was, this guy reminds me of me when I was young, I'm all in, you know, tell me how much capital you need, and I will give you more. I will give you more, and go after the opportunity, I believe in you, I'm not here to police you, I believe in you.

So in that sense, it's quite different. Now, there's teams at SoftBank, many of whom I know, and some of whom I've recruited and mentored, they're all terrific, they're every bit as good as partners at Sequoia or whatever, and they do things on a much more conventional basis, but on a smaller scale. What sets SoftBank apart, what SoftBank is all about, is these kind of amazing visionary bets, spectacularly big and mostly successful bets that Son San makes, and that's what's up.

And you also pointed out the interesting contrast, that when you raise a hundred billion dollars, you can't all invest it in so-called future singularity projects.

Certainly not at the time.

And you're really investing it in things which are much more common.

Now with AI infrastructure, maybe you can deploy that kind of money, because you look at Mukesh Ambani and his pronouncements recently in Bombay with Jensen Wang and building these mega data centres. Now, there you're talking about real estate and these massive warehouses. And then on top of that, you buy real estate, you construct these data centres, and then very expensive infrastructure.

That's where Jensen comes in, in these Nvidia chips. Each chip can cost in the region of $40,000-$50,000. So that's massively capitalised.

So if you had a hundred billion dollars to play with today, maybe you can think about it. But that's the curse of being a futurist. I mean, frequently you're too far ahead of your time.

And from your own meetings with Jensen Wang, how would you, I mean, how did you see him then versus, of course, now he's in the rock star category of.

Yeah, he's the ultimate rock star. I mean, he even dresses like a rock star with that leather biker jacket. I mean, look, he again is yet another visionary.

His story which is fairly well-known, but I talk about it in the book, is these GPUs, graphics processing units, which is what was used, still is in video games. And he had the vision. Masa saw it too, by the way, because the whole chip engineering is architecture is very near and dear to his heart in terms of re-engineering those chips to make them general purpose graphic processing units.

He saw that very early and man, has he been successful. It's just been amazing, amazing to watch. And there isn't a competitor inside.

Yeah. So if I were to ask you about now the landscape or the lay of the land. So in the book that you write about, there was a certain wave of, let's say, companies that were tech-led.

And you also talk about the funny side of it almost, I mean, a pizza company or We Work, which I mean, a normal person would struggle to fathom what's the technology in that. And yet they're positioned as technology companies, funds like yours were investing in them. So let's say that was a phase.

What is the kind of phase that we're in today, if we are?

Yeah, I think if you're talking about 2021, which is probably the period of peak high, two points I'd make. One is that was as much, if not more of public market phenomena. I mean, I think the number of IPOs in 2021, second half of 2020, and then spilling over in 2021 is like north of 1500, I mean, of which maybe six, 700 was SPACs.

I mean, a lot of those deals were disastrous. I mean, we work when public, we have SPAC priced at $10, ended up bankrupt, which means equity is worth zero. So a lot of accidents and the market still hasn't recovered from them.

India is a thriving IPO market. The US IPO market still hasn't recovered. So there isn't much by way of hype and excess in the public markets.

Higher flyers like NVIDIA. NVIDIA is not outrageously valued. If you look at a company.

It's valued lower than a lot of Indian tech companies.

Yeah, but I mean, it's got the margins and it's got the growth. You're not valuing a dream, it's real cash flow and real growth prospects and a fantastic macro trend. And it's got, by virtue of its technology, it's what Jensen described when he spoke in India, that CUDA layer of software that kind of people can build on and get hooked on and not easy to break away from.

So a lot of protective moats too, not a competitor in sight. I don't believe those companies that NVIDIA at 35, 40 times earnings is overvalued. Sonsan publicly said he thinks it's a screaming buy.

He thinks it's cheap and he may well be right. But where you are seeing signs of high kind of what I call FOMO investing is with private companies in the AI space. Artificial Superintelligence, that's my favourite because literally, one guy, I'm sure he's an extraordinarily bright individual, breaks away from OpenAI, what I believe he was the CTO, announces this company and he instantly raises a billion dollars at a five billion dollar valuation and the people clamouring to get in.

And there are a lot of those. And even with OpenAI is obviously much more established, its profitability remains to be seen. It does have competitors, got an open source competitor, Lama, which is Meta.

So it remains to be seen how that unfolds. But the hype around that deal even at 150 billion is quite remarkable. I mean, the people who SPVs have been set up for investors to invest were then selling secondary pieces at a premium.

That's FOMO investing. There's a little bit of that going on.

So, of course, the principles of, let's say, excesses, I guess, would remain with every cycle or every way. So that, I guess, continues. So you're saying that that world that we saw then, the investments.

We're not there yet.

We may never see that again?

No, no, no. Of course, we'll see them again. That's the one thing with certainty.

Bubbles, when you're in them.

You don't know it is.

No, no, no. You can spot bubbles. I think, I mean, I've been in these markets for 30 years.

I think I can spot bubbles. That doesn't mean I know how to trade bubbles. I mean, my favourite example of that is one of the most people would recognise him and agree that he's one of the greatest investors of all time, Julian Robertson.

Julian identified the tech bubble and he was right eventually. But by the time he was right, he was out of business because he just so hopelessly underperformed the market. I think for almost two years that people just lost patience and he himself, I don't know if he lost his conviction.

I haven't talked to him but that's the challenge of investing.

Do you invest yourself in public markets including in countries like India?

Not with any degree of success. I have to say now on a personal basis, I play with things a little bit. But particularly at my age, it's much more kind of index funds and bonds and occasional private investment.

Including in India?

Not that much in India. I haven't been that active in India. I'd like to be to be quite honest.

I haven't spent as much time as I'd like to and I'm very keen to do that in the coming months.

And I mean, are you naturally attracted to technology and technology web sectors?

Only because I've worked alongside one of the greatest technologists and some extraordinarily bright people in the world of technology. My old friend Nikesh Arora and have learned a thing or two and still have connections in the valley and I still see a lot of flows. So yes, I am probably kind of over-indexed in terms of my interest in the world of technology, even from an investment perspective.

So your background, I mean, you're from Delhi and you grew up there and both your parents were doctors? Yes. And how is that?

Do you think that's made you, let's say, more careful? Because in the latter part of the book, you do express reservations about some of those investments and all that. Is that something that you think comes naturally or came naturally many years ago?

Or is that something that you learned, let's say, in Wharton or how to be careful about investing? So really, I mean, is it a philosophy? Is it learned?

It's more a personality trait. Some people are inherently kind of exuberant risk takers. I'm not one of them.

So I don't think it's much more complicated than that. Nothing most people will relate to that. I mean, the people who genuinely enjoy gambling, I don't.

And at some level, if you're creating in and out of financial markets, there is an element gambling.

And you don't necessarily connect that with your growing up or where you come from?

No, not really. I mean, there are plenty of people who come from very humble origins and who are extraordinary risk takers.

So what is then risk-taking? I mean, in all the people that you've met, including entrepreneurs and you described Master Yoshison, who's obviously the biggest risk taker of them all, at least as we know. So how does one, I mean, is there a process to it?

Is it purely something that you grew up with?

Well, there is trading instinct, personality traits, I think has a lot to do with the psychological aspects of trading. Sometimes it's very different in as much as when you think about Masa as a risk taker, you have to go back to the earlier statement I made, which is his self-characterisation, which is, I'm a crazy guy who lives in the future. I'm a crazy guy who bets in the future.

If you're living in the future, you're sort of reading tomorrow's headlines. It's not a lot of risk if you can read tomorrow's headlines. So the way his risk-return calculus is fundamentally different, not something you really want to copy.

Beyond that, I don't have a lot to say, originally to say beyond what's been written in so many investment manuals, books already, but there's personality traits that come in. Daniel Kahneman, God bless him, is one of the most influential books I've ever read. He won a Nobel Prize for making the point that most individuals are risk-averse.

People do not see the world as binary. The gain associated with a coin flip, making money, $10 is not the same as the loss. The coin lands the other way, losing $10, that hurts disproportionately more.

That's how human beings behave. So that element of psychology, I'm very keenly aware of that and it impacts my investment choices. And I think people need to kind of be aware of that when they make their own investment choices.

And are there examples where you felt you got something totally wrong or right and only perhaps in hindsight because of the way you think about things? And maybe it's nothing to do with where you're from or how you grew up, but the way, let's say, you approach a certain problem statement or an investment thesis.

I tend to be fairly coldly analytical and because I'm not taking flyers, I've lost money on these plenty of times but it's always been kind of on spec. I'm venture investing, you sort of assume that there's a kind of a maybe a 10% chance that it flies and you just hope you've made enough bet that some of those will kind of come good. And I've got more than my fair share wrong.

So I can't really come up with any single, I don't know, I don't have any precious nuggets to kind of give you.

Of things you got wrong.

Well or spectacularly right, there's plenty I got wrong but kind of give you the type of insight you might be looking for.

When you got something wrong, would it be because you misread the entrepreneur? I think you quoted example, for example, I'm not saying they were you signed off on them but they were companies which where the entrepreneurs clearly, I mean, were up to something, there was problems in their accounts and so on. So that's one kind.

The other is where the business itself just doesn't hold and it collapses because maybe there was just air, there was too much air pumped into it.

Yeah, I mean look, I mean that happens all the time. Too much air pumped into it, you know, WeWork is the poster child for that, right? And look, I mean, Masa's public statement was, you know, God bless him for saying this.

Very few people have the humility to say this. He said, I may be as guilty. In fact, he might have said, I may be more guilty than Adam Neumann for that outcome.

So yeah, I mean, you give a company too much money and Adam as a real estate business, he was on to something, you know, millennial choices with respect to how people work, how they live. That's a legitimate trend in creating a real estate model that caters to that is fundamentally sound. Where of course, that went wrong is it was it should never have been valued as a technology company and he was definitely giving too much capital, too much leeway.

But the amazing thing about Adam Neumann is he's back and he's being backed to do much of the same thing and he's being backed by technology investors. Which is strange credibility for me but it's happening.

And I'm sort of in a way coming back to that question that, you know, when you start infusing technology or adding a technology layer to things and I thought that was a phase that's gone but and you're really saying that that phase is not gone because people are still able to do that. I mean, create a technology and then position it.

Adam is one of a kind. I'm not sure anyone, I'm not, you know, it was remarkable what he pulled off in the first place, even more remarkable that he's been able to pull out again. There's a side of me that he did nothing wrong, he did nothing illegal, I don't believe he did anything immoral.

I just want to be very clear about that and there's a side of me that just admires him for the sheer audacity of being able to do this not once but twice bouncing back and can I wish him luck.

When you wrote this book, were you thinking of, I mean, is this the one story that you wanted to write about? Is there something else that you?

I want to write lots of stories, I want to write fiction. They're much easier to write, you have a lot less accountability. You don't have to worry about how you describe people, how the way they might react, whether you're in keeping with your NDAs, etc.

So fiction, you have a lot more freedom, you can exaggerate. I mean, the beauty of this story, real story is some of the things were so wild, you would stretch to kind of make it up. So in that sense, this book was lend itself to a non-fiction type, business type thriller but no, to answer your question, I do want to write fiction, that's where I'm interested.

And would that be in the realm of finance?

It probably will pick up elements of that because as a writer, you're always at your best when you're drawing on, you're always most credible when you're drawing on your own experiences and since mine are skewed towards the world of finance and technology, I suspect that will have a lot to do with it and I should say the world of writing because being immersed in that world was just an enormous late-life learning experience for me.

And amongst my last couple of questions, so I'm sure there are people like you in your world and I met a few of them as well who want to write about their world, which is striking deals, maybe the private jets, going to Turkey for a deal, coming back the same day for a family function. It sounds quite glamorous but as you concluded maybe it isn't after a point but what would you advise them? I mean, would you say write your story?

I never read those stories because I don't read non-fiction generally. I actually don't read books written by people like me. I'm not doing a very job of promoting my own books but to be quite honest, most of the time they tend to be boring, they tend to be self-aggrandising and who knows maybe people will say that about my book but no, I mean unless you've got kind of a unless there's something more that you have to say about life, don't bother.

And to me the most meaningful feedback I get, one of the reviewers made the point which I think is exactly the right way to think about my book. My book is not binary. I'm not telling you that all the things I did were great.

I'm not telling you you should be like me or look at me, I was so cool. Maybe that's what you take away from it but that says something about you. No, but you have a good thought story.

But I end on a fairly philosophical note which is and then coming back to the critique it was actually in The Economist made the point that but this could equally be the point is equally the vacuousness of the pursuit of money. And so it's not as cool as it seems and kind of make your own conclusions. I'm not, it is not binary.

I'm not binary in terms of how I talk about people there, people make their own conclusions. There'll be people who love so-and-so and admire him as I do and then other people who think he's a reckless gambler, you decide. No and you end with Tolstoy which is I mean coming to the full circle.

How much land does a man? Yeah, exactly and that's going to tie into the money trap and to the extent there's a theme to that book it's a little bit. To the extent there's a message that people should unpack it's that as opposed to I mean look this is so cool or any of that.

I mean even when I'm in a plane the reason I describe that there's a point to that which is as cool as it is to be in a G550 most people who are in that situation are thinking about oh my God look at the dude next door he's got a G650 and that's the money trap.

Yeah and I think you talk about how Master Yoshida has a bigger newer aircraft.

There's always someone with something that you know kind of is bigger or flies faster or lasts longer or whatever. Alok, it's been a pleasure.

Thank you. Thank you.

Good note to end on.

In this week’s The Core Report's Business Books Sama spoke about his transition from a successful career in finance to becoming an author, and what he learnt along the way.

Rohini Chatterji is Deputy Editor at The Core. She has previously worked at several newsrooms including Boomlive.in, Huffpost India and News18.com. She leads a team of young reporters at The Core who strive to write bring impactful insights and ground reports on business news to the readers. She specialises in breaking news and is passionate about writing on mental health, gender, and the environment.