Scooters Sold but Not Delivered? Ola’s Registration Gap Fuels New Scrutiny

Ola Electric’s registration backlog isn’t just operational. A sales-registration mismatch, vendor disputes, and legal gaps raise deeper questions about compliance and investor transparency.

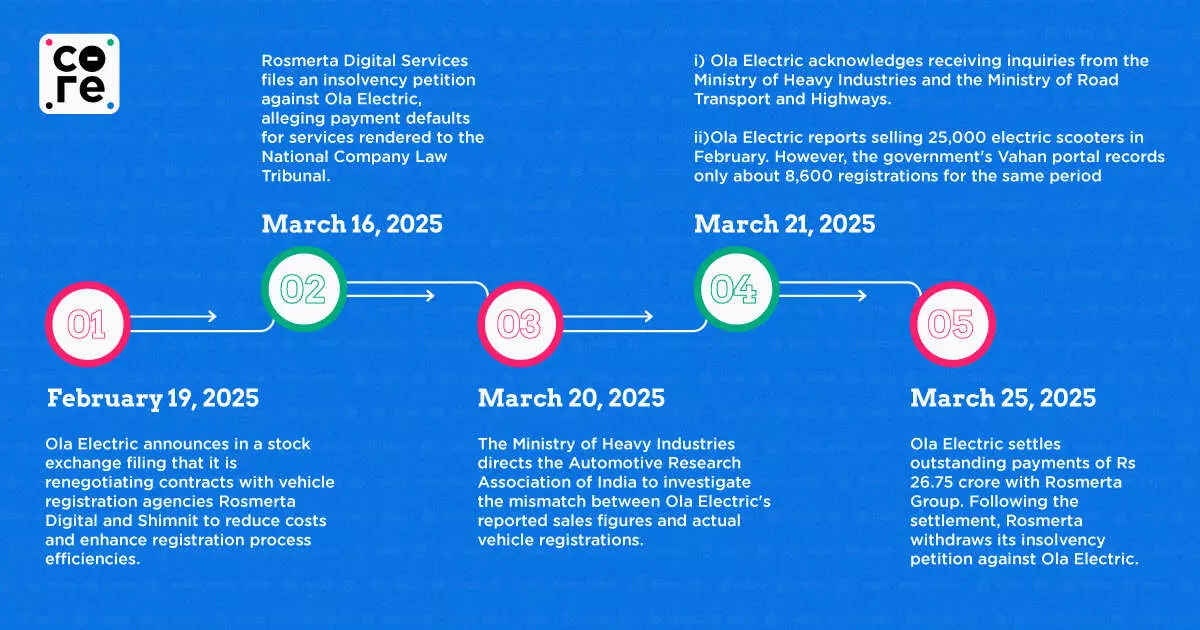

Nearly a month after Ola Electric told stock exchanges it was renegotiating contracts with its vehicle registration partners — Rosmerta Digital Services and Shimnit India — the company finds itself under the regulatory scanner.

On March 21, 2025, Ola disclosed in an exchange filing that it had received formal queries from the Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI) and the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH). The government asked the company to explain why its claimed February sales of 25,000 electric scooters didn’t align with the 8,689 registrations recorded on the VAHAN portal — a discrepancy too large to ignore.

Ola, in its filing, offered a justification:

“The temporary backlog in February was due to ongoing negotiations with our vendors responsible for vehicle registrations. This backlog is being rapidly cleared, with daily registrations exceeding 50% of our three-month daily sales average. 40% of the February backlog has already been cleared, and the remaining will be fully resolved by the end of March 2025.”

But that didn’t stop the questions. In another filing on March 21, the company confirmed it had received two official emails: one from the MHI on March 11 and another from MoRTH on March 18. The ministries asked Ola to not only clarify the mismatch between registrations and reported sales, but also media reports all...

Nearly a month after Ola Electric told stock exchanges it was renegotiating contracts with its vehicle registration partners — Rosmerta Digital Services and Shimnit India — the company finds itself under the regulatory scanner.

On March 21, 2025, Ola disclosed in an exchange filing that it had received formal queries from the Ministry of Heavy Industries (MHI) and the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH). The government asked the company to explain why its claimed February sales of 25,000 electric scooters didn’t align with the 8,689 registrations recorded on the VAHAN portal — a discrepancy too large to ignore.

Ola, in its filing, offered a justification:

“The temporary backlog in February was due to ongoing negotiations with our vendors responsible for vehicle registrations. This backlog is being rapidly cleared, with daily registrations exceeding 50% of our three-month daily sales average. 40% of the February backlog has already been cleared, and the remaining will be fully resolved by the end of March 2025.”

But that didn’t stop the questions. In another filing on March 21, the company confirmed it had received two official emails: one from the MHI on March 11 and another from MoRTH on March 18. The ministries asked Ola to not only clarify the mismatch between registrations and reported sales, but also media reports alleging the company’s non-compliance with Trade Certificate regulations — a basic requirement for any vehicle delivery operation in India.

Under Rule 33 of the Central Motor Vehicles Rules (CMVR), manufacturers and dealers must obtain a Trade Certificate from the local RTO to transport, display, or deliver unregistered vehicles. Operating a showroom or delivering a vehicle without this certificate is a regulatory violation.

A Compliance Breakdown?

What began as a supposed corporate strategy to reduce vendor costs is now spiralling into a larger probe involving regulatory compliance, revenue recognition practices, and possible violations of motor vehicle rules. And Ola’s explanation — that it’s simply catching up on a temporary backlog — might not be enough.

To understand how the investigation snowballed, one has to rewind to February 19, 2025, when Ola Electric filed a seemingly routine update with the stock exchanges. The company disclosed it was renegotiating its contracts with two of its primary vehicle registration vendors — Rosmerta Digital Services and Shimnit India. The stated goal? “To reduce cost and enhance registration process efficiencies.” It added that due to this “ongoing optimisation,” registration numbers on the VAHAN portal for February would be “temporarily impacted,” but sales remained strong.

At the time, the disclosure barely made headlines.

That changed on March 7, when Bloomberg published a report that turned regulatory attention toward Ola. The story revealed that Ola Electric was operating hundreds of offline stores without the mandatory Trade Certificates required under India’s Motor Vehicles Act to sell or deliver vehicles. According to Bloomberg’s investigation, out of roughly 3,400 Ola Electric outlets listed in VAHAN data, just over 100 had valid trade certificates.

Suddenly, what had been framed as a vendor optimisation exercise began to look far more serious: a systemic compliance lapse, potentially affecting thousands of scooter deliveries.

The company’s February 19 filing now appears more consequential in hindsight. While Ola did indicate a likely dip in registrations, it made no mention of vendor disputes, legal complications, or trade certificate gaps — all of which came to light only weeks later. This has triggered questions about operational practices, timeliness and adequacy of disclosure under the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) regulations.

According to multiple legal and automobile industry experts, as well as two sources familiar with Ola’s internal operations and a senior dealership manager, The Core spoke with, Ola’s explanation only raises more questions than it answers.

At the heart of the issue is rule under Indian law: a vehicle cannot be delivered to a customer unless it is registered. This is not a grey area.

The Numbers Just Don’t Add Up

According to Rule 47(1)(iii) of the Central Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989:

“In case of a motor vehicle, purchased as a fully built motor vehicle, which is being registered in the same State in which the dealer is situated, [registration] shall be made by the dealer, prior to the delivery of the vehicle.”

This means that if a vehicle is not registered, it cannot be handed over to a customer, even if it’s fully paid for or booked in advance.

Yet, Ola Electric continues to maintain that it sold 25,000 scooters in February.

The problem? VAHAN data, sourced from the government’s portal, shows only 8,689 vehicles registered during that month. That leaves a gap of 16,311 units.

According to a source close to Ola’s operations who spoke on the condition of anonymity, those 16,311 scooters were not registered in February, and hence were not delivered. “The backlog is real,” the source confirmed. “The delay in registration caused delays in handover to customers, which also led to escalations and complaints across Ola Experience Centres.”

If Ola did not deliver those scooters, how could it record the revenue from their sales? Ola’s Red Herring Prospectus (RHP) — filed with SEBI before its public listing — leaves little room for doubt on this front.

As per Page 281, Point 3.5 of the RHP, under the section titled “Revenue Recognition”, the company explicitly states:

–“Revenue from sale of products are recognised when control of goods are transferred to the buyer, which is generally on delivery for domestic sales.”

–“Revenue is recognised upon transfer of control of promised products or services to customers at an amount that reflects the consideration the Company expects to receive in exchange for those products or services.”

–“A liability is recognised where payments are received from customers before transferring control of the goods being sold.”

In simple terms, if a customer has booked a vehicle or paid an advance, but not received it, Ola cannot count that as revenue.

That brings us back to the February numbers.

With only 8,689 scooters registered, and therefore, by legal definition, delivered, Ola should not have been able to book revenue for the full 25,000 units it claimed to have sold. Unless those vehicles were somehow delivered without registration, which would raised questions on compliance violations under the CMVR and the Motor Vehicles Act.

The claim of “sales” begins to look not just questionable, but potentially misleading.

Aviral Kapoor, partner at Alagh & Kapoor Law Offices, explained that if thousands of scooters were not actually delivered by month’s end (March), regulators could interpret the discrepancy as misleading financial data. Under SEBI rules, any false or incomplete disclosure that influences investor decisions can be treated as material, particularly if it concerns more than 2% of turnover or net worth, which this case likely exceeds.

Separately, a complaint to SEBI and transport authorities last month, written by a road safety activist named Kamaljeet Soi, accuses Ola of misusing privileged VAHAN portal access to issue temporary registrations without actual delivery or RTO approval, potentially violating the CMVR. The Core has seen a copy of this email to SEBI and other regulatory authorities.

“If proven, this could expose Ola to strict penalties, including suspension of trade certificates, fines, and even criminal liability for unauthorised system access. Past Indian precedents show regulators can blacklist vehicles, impose hefty penalties, and in serious cases initiate legal action against directors for fraudulent practices,” said Kapoor.

Ola’s In-house Registration Gamble

Ola Electric found in this registration backlog because of the company’s direct-to-consumer (D2C) sales model — a strategy that once set it apart from legacy automakers.

Under this model, Ola bypassed traditional dealerships entirely, allowing customers to book scooters online or at company-run experience centres, with the entire process — from ordering to delivery — handled in-house. The idea was to control pricing, customer data, and margins. But unlike Honda or TVS, which rely on their dealer networks to manage compliance-heavy tasks like vehicle registration, Ola had to handle this burden at scale, and across the country.

According to a source close to Ola’s operations, this turned out to be a logistical nightmare.

“It is difficult to work with so many RTOs, in one go, and the plan has always been to move to an in-house registration system eventually,” the source told The Core, referring to the fact that Ola had to work with more than 1,500 Regional Transport Offices (RTOs) to clear scooter registrations from both online and offline orders.

That’s where third-party registration agencies came in, specifically Rosmerta Digital Services and Shimnit India, who helped Ola interface with various state RTOs, handle documentation, and manage registration logistics in the absence of local dealerships.

A second source aware of Ola’s operations added that setting up relationships with more than 1,500 RTOs when it began delivering scooters in December 2021 would be cumbersome, hence it chose to work with third-party vehicle registration providers. At the time of launch in late 2021, the company was prioritising speed of delivery over other operational issues, the source said.

“Rosmerta was plugged into the system — they had strong ties with MoRTH and state-level RTOs and were already one of the largest number plate manufacturers. The facilitation they provided at the RTO level was something Ola just couldn’t replicate in-house,” added the source.

But now, Ola is changing track.

According to two sources privy to Ola’s operational shift (one quoted earlier in the story), the company formally ended its relationships with both Rosmerta Digital Services and Shimnit India by March 2025, and has since begun registering vehicles entirely through its internal system.

“Ola is now building its own capacity to register these scooters, and the company has hired more than 200 workers just for this,” one source told TheCore, adding that “there aren’t any significant opex expenditures for this.”

Still, this move may have come too late.

On March 16, 2025, Rosmerta Digital Services — one of Ola’s two primary registration vendors — filed an insolvency petition before the NCLT Bengaluru Bench, alleging unpaid dues of Rs 26.75 crore. Around the same time, The Economic Times reported that Shimnit India, the other key vendor, was also considering legal action, but the matter was settled behind closed doors before it escalated.

The sudden breakdown in Ola’s registration infrastructure delayed thousands of deliveries, the two sources privy to Ola Electric’s operations added. The Core also learned that both third-party registration providers have “completely stopped working” with Ola following operational and compliance disagreements, adding further strain on an already backlogged system.

A Backlog Cleared, But Momentum Slipping

As of March 31, 2025, Ola Electric has registered 23,430 vehicles according to the VAHAN portal data. This sharp rebound suggests the company has made significant headway in clearing its February backlog. But it also points to something more telling.

Of the 23,430 vehicles registered in March so far, at least 16,311 can be attributed to Ola’s February sales backlog—the gap between the 25,000 scooters Ola claimed to have sold in February and the 8,689 registrations recorded that month. That leaves just 7,119 newly registered vehicles in March.

(25,000 claimed sales – 8,689 Feb registrations = 16,311 backlog; 23,430 March registrations – 16,311 backlog = 7,119 new March registrations)

In contrast, key competitors have posted stronger March performance as per the latest VAHAN data, especially when viewed in the context of the 7,119 registrations by Ola post the backlog:

Bajaj Auto registered 34,863 vehicles,

TVS Motor recorded 30,453 registrations, and

Ather Energy reported 15,446 registrations.

This sharp slowdown in fresh registrations raises new questions about Ola’s ability to sustain sales momentum, even as it claims to have resolved the registration backlog by taking operations in-house.

We have written to Ola Electric asking whether the vehicles registered in March were fully invoiced, delivered, and handed over to customers, in accordance with revenue recognition and registration rules under CMVR. The company has yet to respond. This story will be updated when we receive a reply. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways has reportedly issued a fresh show-cause notice to Ola Electric Mobility on March 21, seeking a new explanation for the continued mismatch between reported sales and VAHAN registration data.

Ola, facing scrutiny ahead of its public listing, insists the registration-sales gap stems from a short-term backlog and denies any violation of rules. But with authorities now examining whether its disclosures, particularly around revenue recognition, accurately reflect actual scooter deliveries, the company may face tougher questions ahead. Multiple investigations are already underway, and legal experts say the outcome could shape how regulators hold listed startups accountable.

As Kapoor, of Alagh & Kapoor Law Offices, put it, “the outcome (of the government investigations) will likely set a precedent for how aggressively Indian regulators respond when a high-profile startup’s public figures deviate from officially verified data.”

Ola Electric’s registration backlog isn’t just operational. A sales-registration mismatch, vendor disputes, and legal gaps raise deeper questions about compliance and investor transparency.