Janus View: Is There An Opportunity For India In Bangladesh’s New Politics?

It would be myopic to write off the chances of Bangladeshi politics undergoing a paradigm shift and new democratic forces taking hold

Even as the Indian economy aspires to become atmanirbhar (self-reliant), last week’s events conclusively show that the financial sector, at least, is thoroughly bhoogolnirbhar (world-dependent). A meltdown of American tech stocks, central bank action in Japan, and news of slowing job creation in the US triggered panic selling in global bourses. The contagion spread to India as well. And, despite projecting inflation in India to stay well below 5% throughout the current fiscal year, the Monetary Policy Committee of the RBI decided to keep the policy repo rate unchanged at 6.5%, thanks to geopolitical and other global risks.

The other major development with a bearing on India has been, of course, the political upheaval in Bangladesh, with longstanding Indian ally Sheikh Hasina being forced out of both office and the country, and an interim government taking over. Sheikh Hasina, as prime minister, had put an end to assorted militant groups in the Northeast setting up base in Bangladesh and staging raids across the border in India. The Islamist Jamaat, all too happy to function as the local cat’s paw of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, had been reined in by the Hasina regime. She also resisted the consistent attempt by Beijing to rope her country into an alliance unfriendly, if not overtly inimical, to India.

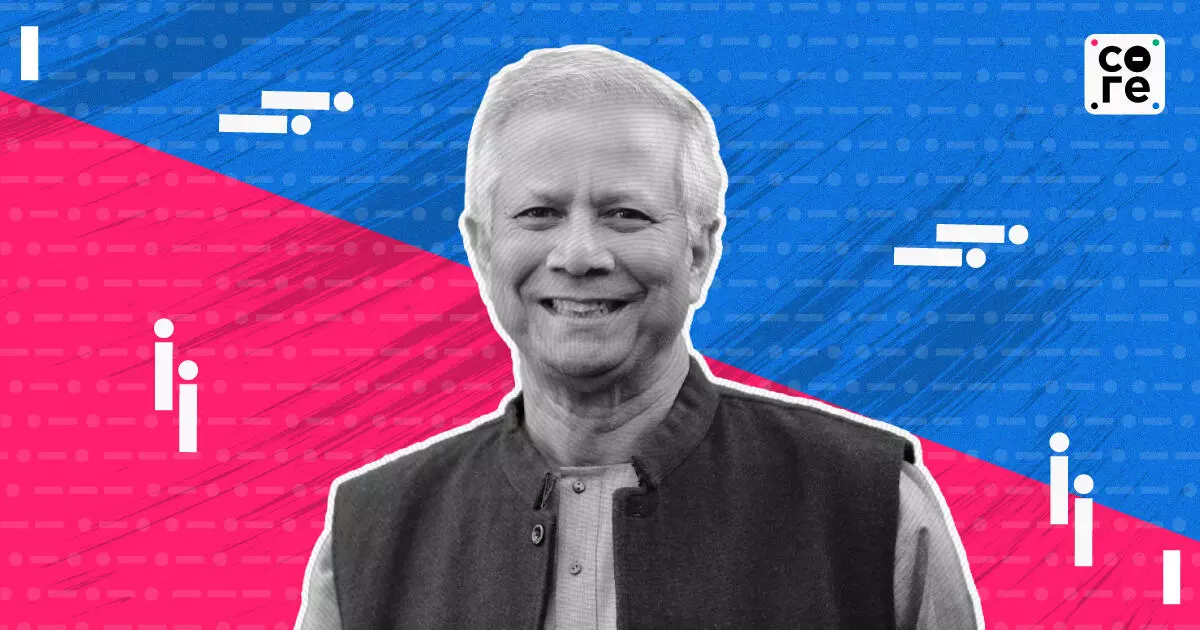

This has led sections of the Indian establishment to see the post-Hasina regime in Bangladesh with hostile suspicion. That would not be less than optimal. Sheikh Hasina’s regime throttled democracy, even as it presided over economic growth, the development of a vibrant ready-made garments industry and growing participation of women in the workforce. She used the authority of the state to suppress dissent, slapping cases against even Muhammad Yunus, the microfinance pioneer, who has done much to alleviate extreme poverty in the country, and innovated financial inclusion and developed entrepreneurship.

That very Muhammad Yunus now heads an interim government. He has called for a new politics and a new political leadership, away from the traditional party structure dominated by Hasina’s Awami League, Begum Khalida Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party, which carries the legacy of the military dictator Ziaur Rahman, and the Jatiya Party, founded by yet another military dictator Gen Ershad, with the Jamaat-e-Islami acting to radicalise society at large. The worry is that Yunus’s respectable persona would only be a figurehead, even as real power is wielded by the Islamists and their political stooges.

While this worry is not entirely misplaced, it would be myopic to write off the chances of Bangladeshi politics undergoing a paradigm shift and new democratic forces taking hold. India should ideally engage with the new regime, and hold out assistance for democratic politics and democratic leaders. The sectarian bent of politics in India would dent the credibility of such an effort, but it nevertheless represents the best course of action for India vis-à-vis Bangladesh.

Last week saw completion of the rescue efforts in Wayanad, Kerala, where rain fury had triggered landslides and killed hundreds of people. Exceptionally heavy rain, sometimes in the form of cloudbursts, has been wreaking havoc in different parts of the country. Himachal Pradesh has been hit badly as well. As global warming continues unabated, creating extreme weather events, such as drought, heatwaves, cloudbursts, and flash floods, it has become imperative to build resilience into the country’s infrastructure.

While all new infrastructure can be designed and built to withstand the disasters that climate change is guaranteed to trigger, it is vital to reinforce existing infrastructure as well. The Coalition for Disaster Resistant Infrastructure (CDRI), a global partnership launched at the Glasgow Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2021 by, among others, the Prime Minister of India, serves as a ready source of expertise on how to go about this.

The CDRI has already worked to help Odisha make its power infrastructure withstand extreme climate events, including cyclones that surpass, in wind speed and precipitation, the ones that regularly plague Odisha's coast. Ever since the super cyclone of October 1999, which killed more than 10,000 people in Odisha and wreaked havoc across the coast, the state has been proactive in managing disasters. It has built strong buildings above the likely waterline of a stormy sea, to serve as shelters and double up as schools in normal times. It has trained a civil defence force that is ready to act when disaster strikes. The state has vastly reduced the human toll of subsequent cyclones. This sensitivity to natural disasters and the potential to mitigate their impact has made Odisha an early mover in reinforcing infrastructure to make it resilient against disasters.

The CDRI has ongoing programmes to strengthen infrastructure in transport, specifically airports, health, telecom and towns, and developed technical standards for reinforcing structures. Its calculations show that every rupee spent on incorporating resilience into infrastructure yields a return that is four-fold, at least.

It offers help in financing resilience as well, although it does not have funds of its own. Building in resilience in new as well as existing infrastructure would add to the economy’s capital spending, and feed growth. Since such activity would qualify for green financing, it could catalyse growth of a market for green bonds in India as well.

Governments at the Centre, the states and cities would do well to draw on the technical and other expertise of this specialist agency on disaster resilience, and start investing to face the future with resilience, rather than passive acceptance of karmic inevitability.

It would be myopic to write off the chances of Bangladeshi politics undergoing a paradigm shift and new democratic forces taking hold

Jessica Jani is a producer and writer at The Core where she covers mobility, sustainability and energy transition. She is based in Mumbai.