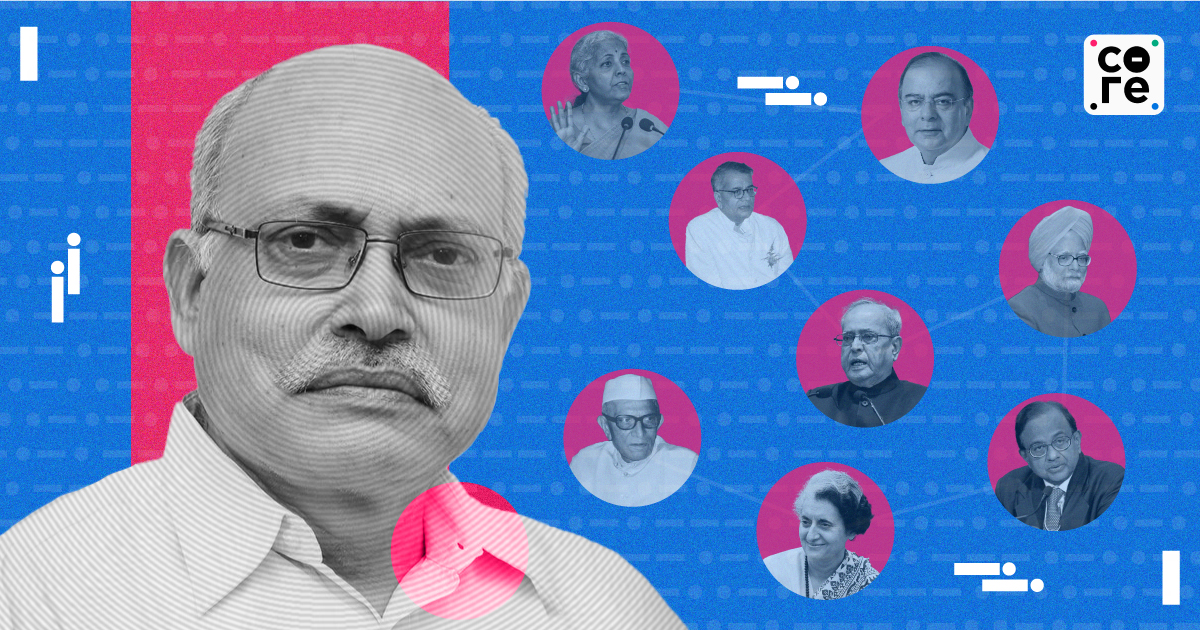

‘So Many Dramatic Ironies': Journalist AK Bhattacharya On The History Of India's Finance Ministry

In his latest book, the veteran business journalist writes about India's finance ministers in the first 30 years since Independence

Veteran business journalist AK Bhattacharya?s second and latest book, India's Finance Ministers from Independence to Emergency (1947-1977), chronicles the story of India?s finance ministers who shaped the country?s economy in the first 30 years after Independence.

Bhattacharya, who was the chief of bureau at The Economic Times in the early 1990s and is now Business Standard's editorial director, delves into the significant impact that these finance ministers made to the management of the Indian economy and to the policy evolution of the government.

Financial journalist, Govindraj Ethiraj, spoke to Bhattacharya about what has changed in the finance ministry since the first 30 years, how some of the institutions that form the backbone of the economy were set up, and the indelible mark that some ministers left.

?If you look at the history of India's Finance Ministry for the last 76 years, you see so many such dramatic ironies that you start wondering if there should be a proper film made on these events and developments,? Bhattacharya said.

?From ?78 onwards you see winds of change blowing in the Finance Ministry,? he said, talking about why he chose the time period for his book. Among the things that have changed is the finance minister?s equation with the prime minister, he explained. ?During those days the finance minist...

Veteran business journalist AK Bhattacharya’s second and latest book, India's Finance Ministers from Independence to Emergency (1947-1977), chronicles the story of India’s finance ministers who shaped the country’s economy in the first 30 years after Independence.

Bhattacharya, who was the chief of bureau at The Economic Times in the early 1990s and is now Business Standard's editorial director, delves into the significant impact that these finance ministers made to the management of the Indian economy and to the policy evolution of the government.

Financial journalist, Govindraj Ethiraj, spoke to Bhattacharya about what has changed in the finance ministry since the first 30 years, how some of the institutions that form the backbone of the economy were set up, and the indelible mark that some ministers left.

“If you look at the history of India's Finance Ministry for the last 76 years, you see so many such dramatic ironies that you start wondering if there should be a proper film made on these events and developments,” Bhattacharya said.

“From ‘78 onwards you see winds of change blowing in the Finance Ministry,” he said, talking about why he chose the time period for his book. Among the things that have changed is the finance minister’s equation with the prime minister, he explained. “During those days the finance ministers had the courage of conviction to disagree with the prime minister and if the prime minister was still insisting on what he wants to be done then the finance ministers would quit,” he said. “Now I do not think that we are seeing that part anymore…the finance ministers do not disagree with their prime ministers to an extent where there is a principle difference and on that issue the finance minister decides to say goodbye.”

The book is the first of three volumes. Volume two, which will be out in January 2024, will cover stints of finance ministers between 1978 and 1998.

Here are edited excerpts from the interview:

You are, even as we speak, writing about your observations on the finance ministry and the government. What do you see today? That in many ways is a reflection of all that has happened in the past in the context of India's economic policy making?

The one point that strikes me very clearly is that certain things have not changed even over the last 75-76 years. I mean what has not changed for example is the fraught and stressed relationship between the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Government of India. That seems to be a running story. Although there are stages, moments of truce, and mutual understanding. But the relationship does not seem to be easy even now. If it was Benegal Rama Rau, longest serving RBI governor had to quit because the then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, sort of outlined the rule of the game that RBI is only autonomous to the extent that it is an extension of the Union Government of India.

Now that is a rule that he sort of laid down very clearly when it came to the RBI's power to decide through a board decision

Now I do not think that we have seen any RBI Governor of late put in his papers as such except that you will remember that in 2018, you saw Urjit Patel put in his papers and quit in a day's notice. And the reason that the media knew why he quit was that he wanted more powers to regulate the public sector banks than what has been given to RBI under the law. And also he was worried about the manner in which the centre was drawing on the resources of the RBI's surplus. So these are the two proximate causes,

And what happened in 1958-59

The second point is the political establishment, particularly the Finance Ministry, initiating action against offenders—economic law offenders, those who are violating economic laws now, those still continue to be shrouded in some mystery, doubts and allegations

So I think in both the issues, I find, things have not changed. Where things have changed, there are quite a few areas where things have changed from those days of the 30 years after Independence. And now, for example, the manner in which the government is relying less and less on the kind of borrowing that the RBI earlier would help the government meet. Today, the Government of India has to seek recourse to the markets for meeting its borrowing requirements. So therefore the Government is under greater fiscal discipline, at least on paper, than what used to happen then. Those days, the ad hoc treasury bills could have been issued at any given point in time by the Government when it wanted to meet its borrowing requirements. But now the government is under greater self discipline, so to say, to meet its borrowing requirements.

So I think there are changes, but what strikes me more is that the things that have not changed even now.

I am going to come to the role of the prime minister in the present and the past since you did bring it up. Before that, why did you choose this particular period of 1947- 1977 and stop the clock?

Three reasons. One, it was becoming difficult for me to pack in all the 25 or 26 Finance Ministers that have taken charge of the North Block, in the last 75-76 years in one volume. So I had to create at least three volumes. So therefore you have to bear with me on two more volumes that will come out very soon. So therefore I had to make a division. I chose to have the first volume till 1978, although it says 1977. But it actually ends at 1978.

Now, the second reason why I chose this period is because this is the time when the Congress era comes to an end for the first time in India's economic history. In a sense, from 1947 to 1978, this was an uninterrupted Congress regime with three Prime Ministers and eleven Finance Ministers having presented these 30 budgets.

And the third most important reason is that till ‘78, I do see economic thought informing policy making in the Finance Ministry. The Finance Ministers, by and large remaining broadly of a similar nature, which is building institutions, setting up the rulebook, following a very restrictive protectionist policy, states to be in the business of businesses. From ‘78 onwards you see winds of change blowing in the Finance Ministry. But till ‘78 you see a similar statist economic policy is raising customs duty, tariffs, interventionist policies where excise duties need to be tinkered with, raising income tax rates, not bringing them down, but at the same time building of institutions, setting up a statistical division, setting up the Economic Advisor's office in the Finance Ministry, setting up the Planning Commission, creating many institutions like the Unit Trust of India, IDBI, ICICI, nationalising Imperial Bank of India. So these are all decisions taken in the same spirit, including nationalising Air India. This is the phase when Congress was in command and in charge of statist economic policies. And I saw that from ‘78 onwards, there were changes that were happening. They took their own time before you saw the 1991 crisis and the economic reforms. But the changes started happening from ‘78 onwards. So that is the third reason why I stopped in 1978 and started in 1947.

You talked about the many taxes, I would imagine wealth tax and expenditure tax. And it is interesting that you also point out that the wealth tax that TTK or TT Krishnamachari introduced in 57-58 was only abolished by Arun Jaitley in 2015. That is 58 years. It also says what it takes to remove a law, or rather how easy it is to introduce a law and what it takes to remove a law. And maybe people should think about that when they agitate against other laws.

Fortunately, TT Krishnamachari introduced one more tax, the expenditure tax. Fortunately, his expenditure tax was abolished much earlier. So in a sense that I agree, wealth tax took so many years before it could be abolished. But luckily, expenditure tax over and above the income tax was abolished about three to four years later.

But the thinking was something that we may see today too, right? That people are spending a lot. When you look at maybe something like tax deducted at source, the thinking is that some people are spending more and they are rich people and they should be taxed on expenditure.

Absolutely. There's a section in this book wherein I talk about where TT Krishnamachari got this idea. He got this idea from British well known economist Nicholas Kaldor. Now, his idea was tax expenditure as well. But he also recommended that by all means, tax expenditure, but do not let the overall tax incidence go beyond 45%.

I think you mentioned that BK Nehru pointed out that basically this was now going above close to 90% or the famous 90%.

Absolutely. So the problem was not with the idea, but with its execution. And nobody in the system could actually challenge it because it came from TT Krishnamachari, who was Nehru's favourite Finance Minister. And nothing could be done except protest and live with those usurious tax regimes.

And TTK, of course had to resign because of a scandal and came back a little later again for his second stint, as you have outlined in your book too. Now, let me come to a slightly larger point. So Nehru seems to clearly play, at least in my reading, as someone who is looking at it, maybe at such depth for the first time, in economic policy. Now, the question here is therefore do prime ministers subsequently, including right up till today, play a far greater role in economic policy than we perhaps know or are able to glean?

Well, there is a qualitative difference that I see from what is to happen in the first 30 years and what is happening now. Let me come to the similarities. The similarity is even then the prime ministers would take the final call and even now the prime ministers take the final call on economic policymaking implemented by the Finance Minister. But during those days the Finance Ministers had the courage of conviction to disagree with the prime ministers and if the prime minister was still insisting on what he wants to be done then the Finance Ministers would quit. Now I do not think that we are seeing that part anymore where the Finance Ministers do not disagree with their prime ministers to an extent where there is a principle difference and on that issue the Finance Minister decides to say goodbye.

If you take classic example of John Matthai, India's second Finance Minister who actually disagreed with

That is CD Deshmukh.

CD Deshmukh. CD Deshmukh too after six years had to quit again in the policy difference of how do you reorganise states and in this time Bombay. Bombay was a financial capital even then. So when Deshmukh realised that his prime ministers was not agreeing to the idea of not tinkering with the structure the way the prime ministers wanted to, he decided to quit. So I think that's an era where the Finance Ministers would listen to their prime ministers. They will have to listen to the prime ministers. Prime minister will have the call on the final policy. But the Finance Ministers would have the courage to say: I am sorry, I disagree, therefore I quit.

I think today what happens is that the prime ministers are taking a very keen interest in what is happening in the Finance Ministry. And when the Finance Minister differs with the prime ministers I do not think the Finance Ministers resign.

I do believe that when demonetisation was announced there were a lot of differences of opinion within the Finance Ministry. The Chief Economic Advisor then was not comfortable with this. The Finance Minister was also not clear whether he agreed with it or not. But nobody would actually take a position—that listen, this is not correct, let us not do it or do it in this way. So I think that is a big change that has happened from the first 30 years to the last 15, 20, 30 years.

Remember, even in the case of the bank nationalisation you actually had to see the Finance Minister quitting because the Finance Minister, Morarji Desai was not in agreement with the idea of bank nationalisation. He clearly believed that the social control of banks is a better idea than bank nationalisation. And therefore when he found that prime ministers Indira Gandhi wanted to go ahead with bank nationalisation and therefore he decided that if you want to agree with it and Indira Gandhi prime ministers also was very comfortable with the finance ministry leaving the scene at this point in time. And so the prime ministers took charge of the finance ministry and implemented the idea and the concept of bank nationalisation. So I think that's a big difference that has happened in the 30 years and now.

You've talked about John Matthai in detail and you've talked about how brilliant he was even in academics. Now how would you see his decision to fight against the setting up of the Planning Commission with what happened more recently, which is to disband the Planning Commission and have the NITI Aayog?

It is a very interesting thought that the Planning Commission was not set up under an Act of Parliament. Even Nehru believed that it is better to set it up as a cabinet resolution. So it became an administrative decision of the government. So therefore he did not use a parliamentary law to create it. So the Planning Commission, as long as it existed till 1st January 2015, was operating as a government department not created under a law. Therefore the Modi Government found it relatively easy to dismantle it because it was not under an Act of Parliament. It was only a government decision carried out through a cabinet resolution.

So I think while the birth of the Planning Commission itself was a little bit

That's interesting. So if you were to look at this whole period again, maybe more tending towards the late 70s rather than the early part, India became inward looking, which is manifested through many of these things that you have talked about, including raising tariffs, including raising duties, and maybe perhaps looking at business in a certain way. And maybe that was triggered by the Haridas Mundhra scandal or maybe something else. If that was the case, do you think that there is one or two individuals specifically who led to it? Were they finance ministers or was it top down in that sense? Was it the Nehruvian way of saying that this is how we should be as an economy, this is the level of taxes, this is the level of protection, this is the level of, let's say, focus on businesses?

I think the answer to your question is that both. At a certain level there was general broad political agreement, except probably views of the Swatantra Party or the Justice Party, which got dismantled. You know, those were ideas with which there was general agreement among the political classes that these are decisions that are needed to be implemented.

So Congress, whether it had the majority or the full majority, did not make much of a difference. They went ahead whether it is a question of raising income tax rates or whether it's a question of raising customs duty or setting up state owned financial institutions, taking over Air India and Imperial Bank of India and creating a state bank behemoth called the State Bank of India. Now, these are all decisions that the Congress governments took and there was not much opposition to those decisions.

But you have to recognise that a very important element during that time was each and every decision was taken after considerable discussion and debate in Parliament and outside Parliament. I mean take the case of the Haridas Mundhra scandal. Now this scandal would not have come about if it had not been raised by a Congress member called Feroze Gandhi who was Nehru's son-in-law. He's a Congress member who raises in Parliament against his father-in- law's government and says that this is not correct. And as a result of which Nehru had no other option to set up a commission of inquiry added by a Chief Justice of Bombay High Court, M. C. Chagla who is given the task of completing the inquiry in one month flat. And just before the budget, he presents that report and even though he is not directly involved in the deal because of his moral responsibility the Finance Minister is asked to go.

And the deal was basically LIC bought shares of Haridas Mundhra's companies and essentially supported them. I mean shades of which we have seen many times later.

Absolutely. And it was done because the stock markets had tumbled after TT Krishnamachari's first budget wherein he had introduced those new taxes. So therefore there was considerable debate within the system to take those actions.

Take the case of even bank nationalisation. As I write in this book, the bank nationalisation move was not decided in one evening. It was discussed and debated in the Congress forums, Congress parliamentary meetings and considerable debate took place before Mrs. Gandhi decided that she does not need the Finance Minister and she needs to change the Finance Minister so that she believes that she can take that decision on nationalising 14 banks. So she did take that decision finally but only after a lot of debate and discussion took place within the party, within Parliament and outside Parliament. So I think that is something that you must recognise which distinguishes that 30 years from what is happening now in the last many years.

But Indira Gandhi also became Finance Minister in 1969 and she was the first Prime Minister to do so.

Yes, she took charge of the Finance Ministry because she felt that she would be in a better position to implement that bank nationalisation decision. And to also take political credit and which she did her party and she herself made political gains by the bank nationalisation move.

And if I were to go back now and look at all the Finance Ministers that you profiled in this period, how would you rank them in terms of contribution?

I know it's a tough one to do, but there are some obvious ones and you've mentioned that already setting up of institutions, which let's say TTK, though he resigned in disgrace in the first round, he came back in the second round and did a lot of institution building, including institutions we see today UTI and IDBI and GIC and so on.

Maybe CD Deshmukh in his time set up the NSS, moved the ISI, the Indian Statistical Institute for estimating income. He set up the Central Statistical Organisation and so on. So that is another kind of nation building. He also worked on revamping the Company Law, something we are still constantly talking about and struggling with. So what's your pecking order like?

My Finance Minister in this 30-year period would be CD Deshmukh because he came in at the helm at a time when India was a young country just about four or five years after Independence. He built new institutions, built new laws. He brought in the concept of Finance Commissions, which actually laid the foundation for fiscal federalism. And he set up a statistical system. He brought in from the World Bank, a man called Mr. Anjaria to look after the Economic Advisor's office in the Finance Ministry, which mind you, was a role that was sought to be played by the Planning Commission. But Deshmukh decided that the Chief Economic Advisor's job should be in the Finance Ministry. So all those institutions, even the State Bank of India idea as a former RBI Governor he was not very comfortable. But then as the Finance Minister, he went in and did it. So I think it is CD Deshmukh, in spite of the fact that he did raise duties, he did raise customs duties, but he was a statist Finance Minister but at the same time, I would say for a young country which has just got its independence, I would rate CD Deshmukh’s performance as the Finance Minister—he made probably the biggest contribution to economic lawmaking, economic governance in India.

I have a related question. But before that, there's another interesting thing you pointed out, AKB. The similarity between CD Deshmukh and Manmohan Singh in their path through the Reserve Bank and the University Grants Commission and then to the Finance Ministry.

Yes, it's remarkable how things happen. There are two things. The first thing is that you mentioned how CD Deshmukh, who was the RBI Governor, was made the Finance Minister and then he went to UGC. But a different sequence—Manmohan Singh was RBI Governor first and then he came to UGC, and then he became the Finance Minister. Different circumstances, but clearly the sequence is very, very similar. There's another similarity that probably has not come through completely, but people can make sense of it because I have given a hint in the book. Which is that T T Krishnamachari, the Finance Secretary under him was H M Patel. Now T T Krishnamachari was the Finance Minister who made H M Patel the fall guy in the entire Mundhra scandal. It was H M Patel, who lost his spotless reputation as being a good civil servant in the Mundhra scandal. Now it is the same H M Patel who came back in 1978 to become the Finance Minister of India.

If you look at the history of India's Finance Ministry for the last 76 years, you see so many such dramatic ironies that you start wondering if there should be a proper film made on these events and developments.

And just to pick up something again from that. We are seeing right now, there is a lot of talk of internationalisation of rupee and linked to that, or maybe triggered by the fact that there was a war in Ukraine and India dealing with Russia on oil, trying to create a rupee denominated world, at least in our trade. And Morarji Desai's first steps in that direction were somewhere in 1960, I would think. Would you like to dwell on that a little bit?

Morarji Desai realised that it is important to help use of the Indian rupee for conducting transactions for Indian exporters and importers. He made some progress. I would not say that the idea of the rupee trade came into being. I think those were half-hearted steps. But what is happening right now is far more revolutionary, I would say. I don't even know whether these are realistic steps or not, but those days getting into a rupee trade was certainly aimed at helping India's trade with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc.

And the other thing, these are terms that have now seeped into, let's say, subsequent decades as well. One was the Gold Control Order, which Morarji Desai is famous for. The second is the Compulsory Deposit Scheme. So what drove these and do we see any remnants of these laws?

Well, Gold Control Law fortunately was abolished by another Maharashtrian Finance Minister like Madhu Dandavate in 1990. And it was mooted first by another Maharashtrian Finance Minister S B Chavan. It was introduced by a politician from Maharashtra, Morarji Desai, which was a disastrous move and I give you a proper account of it, how it really led to the loss of livelihood for so many jewellers and goldsmiths. It continued to be like that and only after about 30 years or so, it finally got abolished.

The compulsory deposit scheme was again a very regressive tax levy wherein a part of your income will have to be deposited with the government at a very nominal interest rate because the government needed resources. So it became like a tax but fortunately Compulsory Deposit— they also moved out of the system by the late 80s.

As you look at the personalities of these finance ministers over time we talked about John Matthai and you've described him as a brilliant individual coming from an academic background. CD Deshmukh again similar…T T Krishnamachari who was a businessman. And the sense I'm getting is that he's perhaps the only businessman in this period at least who renounced everything, became a Finance Minister and seemed to have swung to the extreme left in terms of economic policy at least which was quite contradictory in a way.

Who do you think from this period is the kind of personality we should have as a Finance Minister today? Or what is the amalgam that we should look for or a country like India should want or expect or desire?

In my book, I recount this conversation that Morarji Desai has with Nehru. Nehru is discussing this idea with Desai: why don’t you become the finance minister? And Desai in his usual dry way, he says, “no, I cannot be the finance minister”. Then Nehru asks him, "Why do you think you cannot be the finance minister? What do you think are the qualities of a finance Minister?

So then Desai lists out three or four qualities. And the qualities that I remember, I gave a full account of it in the book is that one, he has to be a party man. In other words, he should be a member of the Congress Party, the ruling party. The second one, he must have a broad idea of finances and money matters. And even if he does not have an expert's idea, he should be open to consult experts to get that opinion. And third, that he cannot be associated with the party's treasury functions.

And I think that a Finance Minister who belongs to the party is certainly in a better position to take important decisions for the government because he should have the best of equations with the Prime Minister. And I say it and I am going to say it in the second or the third volume wherein the difference between Yashwant Sinha, who was one of the best Finance Ministers India has seen and Jaswant Singh was that Yashwant Sinha suffered from a poor equation with his Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee whereas Jaswant Singh in a short time made a bigger impact because he had a very good equation with the Prime Minister.

So a Prime Minister's equation with the Finance Minister and the Finance Minister's equation with the Prime Minister is very, very important.

And remember T T Krishnamachari quit the government when he realised that he could not go to Lal Bahadur Shastri for consultation on economic matters like he could do with Nehru and because Shastri would immediately say that if he comes to him for a consultation, he will refer those decisions to the cabinet. But TT Krishnamachari wanted to discuss proposals with his Prime Minister first before it goes to the Cabinet. So it is very important ,if you look at the last 75 years, that the Finance Ministers who have made a difference are those who have a good equation with the Prime Minister. Even Manmohan Singh succeeded because Narasimha Rao allowed him to function the way Manmohan Singh wanted to function. So I think the most important qualification for a Finance Minister would be how good his equation is with the Prime Minister. And that equation gets better, if he's also a member of the same political party.

AKB, that's a very useful note to end on and brings us back obviously to the present. Thank you very much for joining me. And before you go, a word on when the next volume is out?

The next volume is out in January 2024.

Okay. And what years is that going to cover?

Period will be from 1978 onwards to 1998. Which means you can cover the first stint of Chidambaram and will bring us pretty much to the present.

In his latest book, the veteran business journalist writes about India's finance ministers in the first 30 years since Independence