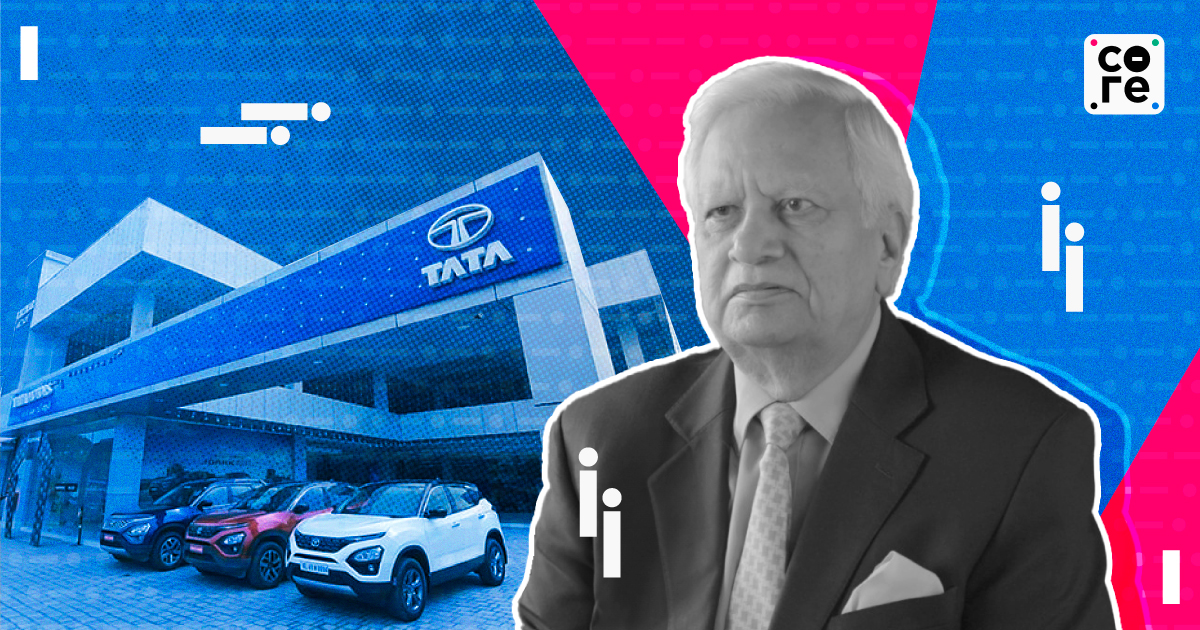

Singular Path Forward, Says Former CEO Ravi Kant On Tata Motors' EV Dominance

Given India's constraints, a company cannot afford to spread its resources across multiple technologies, Kant said.

Homegrown car manufacturer Tata Motors' foray into electric vehicles (EVs) and becoming a market leader, is a story of catching a trend early. The company understood quite early that electrification was the future, and put the necessary resources into it, and the benefits of which it is reaping now. In 2023, the company had over 70% market share in the EV space.

?They have taken the first step, absolute clarity, no hesitation, and they're putting in a lot of resources as far as design, quality, everything is concerned. And that's how they have taken the lead and they want to grow the electric market,? Ravi Kant, former chief executive officer of Tata Motors, told The Core.

According to Kant, given India's constraints, a company cannot afford to spread its resources across multiple technologies. With limited resources, it must select a singular path and concentrate all efforts towards its advancement. ?So many other electric, I don't want to name, but it fritters away energy. It fritters away the focus. Can you imagine that the same model is there in four variants? You have to have procurement, you have to have manufacturing, you have to store them, you have to have dealers,? Kant said.

In this week?s The Core Report: Weekend Edition financial journalist Govindraj Ethiraj spoke with Kant on his book Leading from the Back and on his insigh...

Homegrown car manufacturer Tata Motors' foray into electric vehicles (EVs) and becoming a market leader, is a story of catching a trend early. The company understood quite early that electrification was the future, and put the necessary resources into it, and the benefits of which it is reaping now. In 2023, the company had over 70% market share in the EV space.

“They have taken the first step, absolute clarity, no hesitation, and they're putting in a lot of resources as far as design, quality, everything is concerned. And that's how they have taken the lead and they want to grow the electric market,” Ravi Kant, former chief executive officer of Tata Motors, told The Core.

According to Kant, given India's constraints, a company cannot afford to spread its resources across multiple technologies. With limited resources, it must select a singular path and concentrate all efforts towards its advancement. “So many other electric, I don't want to name, but it fritters away energy. It fritters away the focus. Can you imagine that the same model is there in four variants? You have to have procurement, you have to have manufacturing, you have to store them, you have to have dealers,” Kant said.

In this week’s The Core Report: Weekend Edition financial journalist Govindraj Ethiraj spoke with Kant on his book Leading from the Back and on his insights and learnings from a long corporate career.

Edited excerpts:

You've been at the helm of many companies in consumer products like Phillips, Lohia Machinery Limited (LML), and so on. So why a theme like this (for your book), and what brought you to this theme, and then what made you write about it?

I've been asked to write books on what I did or what happened during my tenure in different companies, but I've been extremely reluctant to do that because I don't want to write about that. Then, about four years ago, somebody told me, why don't you write about your learnings? That made me pause, and I said, okay, why not? Then he suggested, that you always test the limits, why don't you think about testing the limits? And that was the first cue.

Second cue, I got was, again, another close friend, a business associate. I asked him how do you think you described my way of working? And thought for a minute, then he said: Ravi, you lead from the back. And that's when the penny dropped. And I said, okay, so let me go back. What does it mean? Because he was from advertising, I had huge respect for him. I went back and deconstructed the entire thing of what leading from the back means.

I went back to my 50 years of experience, and then I culled out three basic, simple truths. One about myself. First, because you have to talk about yourself, then it is how to build a team. And number three is how together you tackle the task. Because ultimately, as a corporate person, you have to tackle a task. In each of these three, there are three simple things, again, but very difficult to implement.

In the first one, what do I do with myself? The first is to have an open mind. Number two is to take ownership. And number three is to be detached. Sometimes it may seem contradictory. We'll talk about it later. About the team–build trust, be collaborative, leverage strengths. And for tasks, test the limits, look outside, and act up softly.

The question was, how do I make it happen? Then somebody suggested it's good for a parable. And that also set me thinking: okay, what does it mean? I was writing a serious book. I went through some of the books and parables. I said, that's very interesting because my target group was mid-level managers and I wanted it to be a low-priced book so that people wouldn't think twice about buying the book, although it was a somewhat difficult topic.

That's how it came.

Let me begin sequentially. You said first is what do I do with myself? What part, or rather where in your career did you pose that question to yourself first in which, let's say, organisation or task that you were faced with?

When we were going to bidding for, Daewoo Group, South Korea. They don't speak English. An English-speaking mid-level manager was assigned to us. I was standing in the anteroom of the president, just with them, just the two of us. And I thought, as we are doing the due diligence and we want to take over the company, but we are not taking an innate company. We are not taking a piece of machinery. We are taking living organisms. And therefore we must know how these people perceive us or what they want.

I asked him, who do you think you would like to go with? And he said that we would like to go with a European company. I asked him why. And he said that because it will ensure our career, it will ensure our future because we will get technology, we will get this thing, which if you were a closed mind, you would say, no, what the hell? He doesn't know me. If you are full of ego, you will say, he doesn't know me. And why is he saying this? But with an open mind. if you think about it, then you feel that what he is saying is right, because he needs to protect his career, he needs to protect his future. And that one sentence made the whole difference, in our whole approach to taking over. We got everything translated into Korean. We took appointments with all from the president, trade minister, governor, everybody else, and we informed them, told them, look, as Korea had made tremendous progress in technology and in business and all that, but they were lacking in one thing, corporate governance. And Tatas has been doing corporate governance for over 100 years. We had to teach them something, as we were to take something. And the other thing is, Tata Motors was into R&D (research and development), and into well connected worldwide with various things that changed the whole tone. And when my team was coming back after due diligence, they became emotional and said, if the company was to go to anybody, it must go to Tatas. It was not (about) the money that we were offering. It was the way we acted with them with a very open mind, that changed everything, and actually made us win the pitch.

And later, or soon later, you were to acquire Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), which was, of course, iconic in very different circumstances. How did a similar situation play out there as well?

The template was the same. What was our template in South Korea? Our template was: Be a South Korean company in South Korea, not an Indian company in South Korea. It's a subtle difference, but a huge difference. That means you are seeing yourself as part of that scenario, not as somebody going from here and acquiring. You are part of them, and you are therefore looking at the well-being of people. You are looking at the well-being of society. That's the Tata ethos.

And we applied exactly the same template here (Jaguar) also. Here also, we had a very tough problem because the union was very strong, and they were supposed to be leaning towards some others. We had a three-hour confrontation, not a confrontation, but a very tough discussion. They came with an eleven-page or twelve-page questionnaire, and they kept asking questions, and it was eyeball to eyeball. Answers, answers, answers. After all this was over, then my colleague said: Sir, it has gone very tough. I don't think it is going to happen. But something inside me told me that, no, I think we have been very honest, very transparent, and they will accept us.

And lo and behold, two days later, they went to a press conference. They said the company must go to the Tatas. What I'm trying to say is, that it is this kind of attitude that can win over people and which can make things happen and get extraordinary results.

Intuitively, JLR is a company with globally iconic automobile brands. From India Tata Motors is better known at that time, at least, as a commercial vehicle manufacturer. There's no real synergy. As people Tatas are great, but they're only known in India and not outside. What is it that was the clinching point in at least those interactions that you had?

Just taking your point a little further. The president of the dealer association in the US called us a tandoori chicken company, and he said, how can a tandoori chicken company take over iconic brands like this? But we found various things, which I think many people were not aware of, and I'll list out four or five things.

Number one is, although they were not known for quality, I think our predecessor had spent a lot of money and made the manufacturing quality very good. And therefore the products which are going to come out were going to be of high quality. Then their engineering was very strong, and their style was very strong. And the kind of products we saw in the pipeline, we were very enthused that not only what was going to come in the next year, but over the next four or five years, it was strong. And because they were strong in engineering, they could continue to give. The third thing, we found out was that even though the dealers were under stress, their loyalty to the brand was amazing. I have never seen in my life that kind of brand loyalty, that the dealers had for the Jaguar and Range Rover brand. And I thought, if this is the case, and if we were to combine some strengths from Tatas, like our focus on cost and our focus on consumer orientation, then we can make a very powerful thing. I think that's what we discussed. Mr (Ratan) Tata was of course here very involved. And he's the one who suggested that we should look at it.

And finally, of course, it all happened. And Mr Tata and I and some other people went around the US meeting dealers. We must have met scores of dealers. And at the end of the day, people understood who Tatas was, because Mr Tata himself was personifying the group. The same person, the Tandoori chicken person, became a best friend. What I'm trying to say is, while cut and dried, things are fine and they should happen. But I think success depends a lot on other things, the soft issues, how you behave with people, how you deal with people and that kind of thing.

The second point you talked about is building the team either for a task or a company as a whole. But I'm assuming, since you've always been with mature businesses, it could be more sort of fresh teams or renewed teams, or for certain tasks. What are the examples that stand out the most to you as you look back?

I worked in seven companies, each in a different industry, and of which I had no knowledge therefore, how do I succeed? From scooter company to Phillips, from Phillips to Tata Motors, and before that, Titan watches or Hawkins pressure cookers. With some stroke of luck, I got into the new company, but I have no knowledge of it. How do I do? What do I do then? I went alone. I did not go with the coterie of my people, because by going alone, I'm giving them the signal that I am trusting you. I have not brought my trusted people along with me, whom I'm going to trust. That's how we built trust. The main thing was building trust. It takes time. Some people begin to understand you in three months and say, okay, this guy is okay. Some people will take years, some people will take two years. Some people may not trust you at all, but you have to take that chance.

But once you build that trust, they are building a very strong foundation, because then trust leads to collaboration, a strong collaboration. And if you identify people's strengths, so you can understand—taking people's strengths, individual people's strengths, in a collaborative manner, where there's trust pervading, you are making for a very powerful organisation. And you may be thinking that, okay, I'll go from here to there, but this organisation can go from here to there. That is the difference.

In the case of Tata Motors, when you joined, these big acquisitions were still a little away. At that time, it was more about launching, let's say, Nano, which didn't do that well, and Indica or Indigo, which already, came, I think, a little later. But these were existing. But Tata has already transitioned from commercial vehicles to passenger vehicles.

Was just transitioning.

What were the kinds of challenges, then? From the outside, it seemed like a lot of people felt that Tatas would not succeed in the passenger vehicle because they said for decades, it's only built commercial vehicles, many of them out of Jamshedpur, some from Pune, and so on.

Let me go back a little, because I became the CEO of the company a little later, in 2005, I think. For the first six years, I was only in commercial vehicles, looking after commercial workers. That time, unfortunately, the market tanked. And, commercial vehicles have very close connections with the economy and therefore the commercial vehicle market tanked. But in that market itself, we were able to maintain our market share. Of course, we turned in our first loss in the company's history. And that's the kind of thing I confronted or I was faced with when I joined the company. And therefore, how do you make the turnaround? And of course, several things were done.

Cost reduction was one of the key ones. Then new products and changing other things. So many things in marketing and all that. We were able to convert a Rs 500 crore loss into a Rs 500 crore profit in just two years. That was a fantastic thing. And that's how people came together because successful companies also have a lot of egos. People say, no, it can't happen, but it happened to them and therefore you challenge them. Now it has happened. Now let's pull up our socks and do something as a team. And things happened and we came out of the woods and we made a gain.

Then another big thing happened: the introduction of Ace. We don't talk about that. But Ace created a new market, equivalent to the existing commercial vehicle market. That is how big that transformation was, Ace. It was a roaring success.

Ace, for those who don't know, would be a small truck, right?

A mini truck. It's the last mile of connectivity, whether for urban areas or rural areas. And it exceeded all our expectations. We were flabbergasted by the success of this. We had not thought it would succeed.

Where did the idea for Ace come from?

Number of places because one thing was there at that time. Mr Vajpayee’s Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana was ongoing and therefore these (roads) were getting connected. Rural areas and urban areas were getting congested. Then somebody suggested, why don't you have this kind of vehicle? We put together a team and they went around the country. They looked at three-wheelers because this need was being met by three-wheelers. They looked at the need, they came up with a fantastic product called Ace. And again, Tata Motors had this huge reservoir of talent. As far as low price is concerned, the economy is concerned. They came up with this beautiful thing and we launched it. We launched it first in Tamil Nadu. We sorted out all the problems. I remember we launched in Tamil Nadu and it was called Chhota Hathi. What do you call in Tamil? Chinna (Yannai?). It became a roaring success. And we started doing 600 a month. And then somebody said, no, it's not going to sell more and all that. We said, nothing doing, in India, there's no such thing as can't be doing more. We again challenged ourselves, and we reached a level of almost 1,850 per month, just one product in Tamil Nadu, which was our weakest market. As you know, our competitor had a very strong market.

Ashok Leyland.

Yeah, yeah. We did very well and then slowly expanded to the entire south India. And then we took almost 9-10 months to cover the entire country.

And that model continues today in roughly the same form and shape. With some innovations.

It's got variance. It's got variance for the upper side, lower side, horizontal, and all that. We built a whole new plant in Uttarakhand for Ace.

Ace was a success. And you were saying the transitioning to passenger vehicles. Tell us about the team factor that was playing there.

I think the person who spearheaded the Ace project was asked to also spearhead, now the Nano project. Unfortunately, it didn't succeed. But as far as innovation is concerned, it is kind of unheard of. It is almost impossible— to work backward that, okay, it must cost Rs 1 lakh then work backward. And if there was an imaginary car, what would be the different component prices? That's how we started from a white sheet of paper, and then the engineering team kind of looked at it very seriously. We talked to our suppliers. Suppliers played a very key role in that and making it happen. And after that, we did several things, and therefore, it came out after seven years in a different form.

I think it's a tribute to the organisation, a tribute to the excellence of Tata Motors, especially the engineering team.

If I were to just build on that for a moment, if you were to apply those lessons today to any company, including in, automotive, we're seeing so many brand launches, so many variations. What would be the lesson from Nano from then, which we can apply now, as in the good and the bad?

I think the first lesson is to not think that anything is impossible, and you need to therefore work methodically and talk to people. And once you set yourself, as in the third part, test the limit. This is testing the limits of making a car at Rs 1,00,000. How do you make it happen? As I said, we had a white sheet exercise. This is the selling price. Then come back. This will be excise duty on that. Come back. This is the bill of materials, say 70% of that. And if this is the bill of material, what should the cost of tyres be, what should the cost of the engine, what should the sheet metal cost? And then you go and say, if I have to make an engine at this price, what do I need to do? That forces you to innovate. I mean, for innovation. I don't think there's any parallel in the car industry as far as Nano is concerned. It forces you to innovate, it forces you to collaborate, and it forces you to go outside the box. And I think that's what is needed.

The x-factor was missing, which is why it was not successful either because of the looks, the marketing, or the branding.

I think the looks were good. I've still not been able to put my finger on it. The advertising brought lakhs of people into the showrooms, lakhs of people. And out of that, at least 50% of people took test drives. It was quite amazing. And many people out of that put in money, but after that, they didn't come back.

Because there were other models at slightly higher prices.

I don't know. That's why I'm saying I've not been able to put a finger at it. As I said, we were very tough as far as cost was concerned, but of course we took care of people.

The other thing in Nano, which I think is truly remarkable, which has not happened anywhere in the world, is we have built a complete factory in West Bengal. At the last minute, we had to make a very tough decision to move it out from there. We were moving 1,300 kilometers to the opposite side in Gujarat. On one side you are dismantling a factory bolt by bolt, machine by machine, packing it up in a container. Another side you are building another factory to take all that. On the third side, we converted part of our plant in Uttarakhand, which we had built for Ace, into making Nano. And that's how we started making Nano in small quantities. I don't think has ever happened. And it is again attributed to the team, to Tata Motors' tenacity and not giving up on anything and to have made it happen.

If you would say today, just looking back who was missing in that room when suppose you had the whole team of people who designed the Nano, who are very good at, let's say, managing costs, logistics, bringing down prices, and of course, let's say the challenge of then moving the plant because of political reasons. But who would you say, in retrospect, was missing in that room?

I can't think of that. But ultimately, you know, it was Mr Tata's idea that he would like to make a car at that price.

Which apparently was influenced by CK Prahlad's (Fortune At The) Bottom of the Pyramid.

Whatever, I am not going into all that. But he had thought of this in Geneva and he disclosed this a few years earlier in Geneva. And Mr Tata was very involved in this whole thing as to what should be the shape, what should be this thing. He used to personally come, frequently come to Pune, drive the cars in various things, see the thing, have the presentation, very involved in creating. But as I said, I'm not able to put a finger on it.

But, someone was missing, you feel.

I don't know how someone was missing

Or if you were to contrast it with, let's say, the success of Ace or maybe some of the other passenger cars later….

Yeah, it is the X-factor, which you may call, things about which you can't explain. And sometimes some things happen beyond your expectations. You are working the same thing, you are doing the same thing, some things are beyond your expectations, some things are below your expectations and that's what has happened.

In Leading from the Back, you also talk about teams. That's the third factor. How do you bring together a team and the task, the assembling of the team is one thing, and then making sure that the team converges towards a task and usually an impossible task. In Nano’s context, it appears to me that you had no competition except your own, let's say, will do it at a certain point in time and make and take it to the market. How does that happen? I mean, again, instances that you can lean back on where teams have come together, in some cases may be led from the back for impossible tasks.

Turnaround of Tata Motors. The first one was impossible, very difficult. Then putting Cummins engines at the top of the heap as far as commercial vehicles are concerned. Then the introduction of Ace, the introduction of Nano, and the acquisition of a truck company for the first time in South Korea where people are very nationalistic, people don't speak English, and are very proud of themselves, to go and make a success of that. Or then to Jaguar Land Rover. Everywhere it's the team. Everywhere is the team. If you have a good team, if the people are very honest, people are very transparent, there's no kind of politics and all that within the group and all are moving towards one direction and you have support from the top boss, Mr Tata, then I said, nothing is impossible.

That is one thing I've learned from Mr Tata, to think big and bold. I could never have imagined that we'd be making such decisions. It is, I would say the sheer influence or sheer support from Mr Tata, that one was able to decide because if things went wrong, you are still going to be there doing something. And that's how Tata Motors went from 1.9 when I joined the company, a 1.6 or 1.7 billion company to a $39 billion company in the span of 15 years. If the company had not taken such bold decisions, we wouldn't be here.

One of those decisions was to become a global company, which also was sort of facilitated by the time, mid-2000s to the end-2000s. The rupee was strong, and Indian companies were acquiring overseas. The ecosystem was favourable. But that also requires taking bets. And at that time it felt that, okay, let's go outside. What were the kind of different kind of views and how did the teams come together?

At that time Tata Motors was only into commercial vehicles, and commercial vehicles are a very cyclical business. It goes up 40%, goes down 70%, and this is the nature of the beast, so to say. And not only in India, but worldwide. Therefore, if you wanted to reduce the cyclicality, you needed to also put some things which were less cyclical. And that's how Ace came because smaller commercial vehicles are less cyclical and there's some phase difference and go international, go into the car business. This is all part of the same strategy, that if you were to have combined all this, then the whole company would be less cyclical, and therefore you wouldn't have to go through what happened in 1999.

That was one of the things. And because you have a strong resource base in Tata Motors, in people, I think that's the biggest thing. And you have a kind of strong leadership which Mr Tata provided into really thinking big. And that gave me a lot of encouragement. And we put young people, I mean, for example, we took out young people and put them in charge of Ace. The whole team and did fantastically well. We also put a young team in Nano. We also sent a mid-level team to do this thing, due diligence, and all that for Daweoo and this thing. I would say if you give people freedom, if you look at their competencies and strengths, and give them opportunities, I have seen that nine out of ten times it works.

And Tata Motors today, for example, let's say, has 80% of the EV (electric vehicle) market, it is spinning off as a separate company, and so on. Would you say that what you saw then, and were also maybe setting up and the kind of team structures and so on, is also responsible for what we are seeing today?

Sure. I think the current leadership of Tata Motors, whether it is the chairman (N Chandrasekaran) or Shailesh Chandra (managing director at Tata Motors Passenger Vehicles Ltd), they have taken a big bet that electrification is the way. And if and whenever markets change, when the trend changes, then if you position yourself strongly, you have a great benefit because you can go with the wave. And that's what Tata Motors did. They have taken the first step, absolute clarity, no hesitation, and they're putting in a lot of resources as far as design, quality, everything is concerned. And that's how they have taken the lead and they want to grow the electric market. There may be other problems, other things, and all that. And they are always naysayers in society. There are always people saying, this should not be done, this thing India can't afford. But my personal view is that India cannot afford several technologies. We don't have the benefit of that luxury. And therefore, India should choose one and put all resources and just move forward.

When you say different, do you mean hydrogen and others?

So many things, so many other electric, I don't want to name, but it fritters away energy. It fritters away the focus. It fritters away. Can you imagine that the same model is there in four variants? You have to have procurement, you have to have manufacturing, you have to store them, you have to have dealers. People don't understand this, but a manufacturer understands this, and therefore, you're making things very complicated. That's all I'm trying to say. And therefore, with a single-minded focus and purpose, if you go ahead, which I think Tata Motors is doing, it's fantastic. If they move forward like this.

The point that you made is that catching the trend, catching the trend. And you feel that today, whether you use the leading from the back or assembling teams in general, of course, successful companies by definition must be. But in general, do you feel companies are aligned well, to spot trends, to respond fast to them? I'm talking about India now specifically.

I don't want to generalise, but you will see umpteen examples where people who have caught the trend have benefited immensely. I'll give one example of where I've been. Titan Watches, for example. Titan watch has done fantastic things. But one of the key things, which aided Titan Watches then was they caught the trend at the right time for watches, for quartz watches. I was there only for five years, for quartz watches. And because it was heavily dominated by mechanical watches, as you know, HMT was the king with 85-90% market share. Then Titan took the bold risk of being only in quartz watches because there was a trend of people already becoming fashion conscious, and therefore they were already into multiple watch ownership, which were being fed by smuggled watches and things like that. And therefore it caught the trend at the right time and went ahead. And you know, what happened to HMT watches later on.

Later on, of course, Titan went into other retail things like jewellery and various other things. I don't want to comment, but then, because it took the bold risk, it caught the trend at the right time, and it went up.

And you're also saying that, in a way, put many eggs in one basket, like whether it's in the case of electric today, or Ace at that time, or Nano, and then, let's say quartz in the case of Titan, and then for every company will have something. But don't go with five different products and try.

And so catching the trend is an important thing. I mean, there are so many market researches done, whether it's qualitative, quantitative, this thing, that thing, so many things are there. I think you need to look at all that. And with that, you need to add your gut feeling. I think the gut feeling is very important in business in trying to catch the trend, “kya ho raha hai, kya nahi ho raha hai (what is happening, what is not happening), that kind of thing.

Let me ask you then, two questions. One time, at any time, where you felt that you were strong on your gut, but it didn't turn out as well. And the second, where, again, you relied on your gut, but things turned out well.

One was, of course, I'll take Hawkins. Hawkins is a great company. I learned my marketing at Hawkins. We were selling pressure cookers. Then we thought of coming into electrical products, and we had two fantastic products. One was an infrared cooker. Quick time in two minutes, three minutes, you'll cook. The other is a slow cooker, put it overnight. Both are fantastic products, quality-wise, look-wise, performance-wise. We did many things. Many, many things. It didn't succeed. We had to finally close down. Hawkins had to close down. I felt very bad because there were very good products, extremely supported by marketing and sales and everything, but didn't work. Because perhaps the market was not ready, the consumers were not ready to go for that.

But today, you see so many slow cookers in the market. There's no dearth of them, maybe they'll come back again with this. I don't know. But I'm talking about 25 years. It was way ahead of that time.

We used to see Panasonic and those brands.

I think it was way ahead of time, that's all I'm saying. And therefore, perhaps had become maybe ten years later, we would have got it in a better fashion.

That's one, let's say things didn't work out. And on the other hand, where something you feel you were bang on.

Titan. Titan Quartz is a fantastic example. The success of LML is again, a fantastic example of how people were used to one type of product.

Bajaj Chetak.

One type of scooter. I won't name, so scooters. And because I was coming from Titan Watches into LML, I could see the consumer was already changing. And therefore, can you add some bells and whistles and frizz and things like that, upgrade it a little, and make it a little more aspirational. And lo and behold what happens. A 9% market share turns into 32% in a very intensive, competitive, dominant industry. Can you imagine? Because we were able to catch the trend, we were able to do it. Not because you have to do certain things, no question of that. But if you are able to catch the trend, then your success is far greater than you can ever imagine.

Given India's constraints, a company cannot afford to spread its resources across multiple technologies, Kant said.