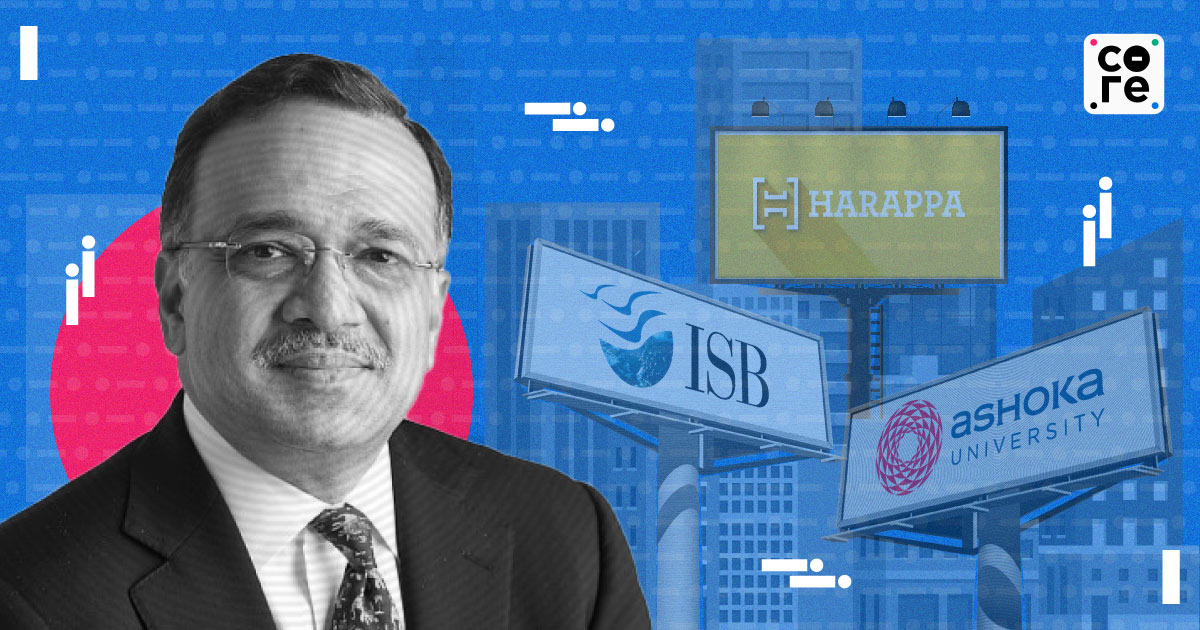

Running Errands To Lego Blocks: How Entrepreneur Pramath Sinha Used His Childhood Lessons To Build And Transform Institutions

Sinha was the founding dean of Indian Business School, Hyderabad, founder member of Ashoka University, and is founder of the online learning institution Harappa Education.

Pramath Sinha, now 59, was a young boy of seven or eight when he played with his Lego set and built structures. Little did the founding dean of Indian School of Business (ISB), Hyderabad, founder member of Ashoka University, and founder of the online learning institution Harappa Education realise how important this engaging and fun occupation would be in his future. Half a century later, many refer to him as an "institution builder," alluding to the diverse organisations he has founded, nurtured, mentored, and advised, particularly in higher education during the previous three decades.

Sinha and I have known each other for several years, but the quality and intensity of our interactions have become far more pronounced in the last few years, ever since he began working in and I began writing more aggressively on the higher-education space, both driven by a conscious realisation that education is the single most serious crisis confronting our country and that unless something is done about it, India will never achieve its full and true potential.

We connected over Zoom on a late June afternoon ? he in his Harappa office in New Delhi?s Okhla and I in Goa?s Panjim ? before the rains in the two cities unleashed their full fury, spreading cheer in Goa and mayhem in the national capital region.

It isn?t just the Lego bloc...

Pramath Sinha, now 59, was a young boy of seven or eight when he played with his Lego set and built structures. Little did the founding dean of Indian School of Business (ISB), Hyderabad, founder member of Ashoka University, and founder of the online learning institution Harappa Education realise how important this engaging and fun occupation would be in his future. Half a century later, many refer to him as an "institution builder," alluding to the diverse organisations he has founded, nurtured, mentored, and advised, particularly in higher education during the previous three decades.

Sinha and I have known each other for several years, but the quality and intensity of our interactions have become far more pronounced in the last few years, ever since he began working in and I began writing more aggressively on the higher-education space, both driven by a conscious realisation that education is the single most serious crisis confronting our country and that unless something is done about it, India will never achieve its full and true potential.

We connected over Zoom on a late June afternoon — he in his Harappa office in New Delhi’s Okhla and I in Goa’s Panjim — before the rains in the two cities unleashed their full fury, spreading cheer in Goa and mayhem in the national capital region.

It isn’t just the Lego blocks. At least three of his childhood and adolescent experiences — and learnings from those — have shaped and influenced what he is today.

Running Errands In Patna

Growing up in Patna in the mid-1960s and early 1970s, he experienced a life that few young children growing up in today's affluent and educated Indian families in cities can relate to, where hired house help executes even the most basic tasks that children routinely carried out in similar socioeconomic circumstances. He and his three older sisters were always running errands, from distributing the books his family published to planning his sisters' weddings. Bearing responsibility and being held accountable for small and large events was ingrained in him and his siblings.

This was in addition to his all-rounded Jesuit education in St Michael’s High School, where he dabbled in everything from debating to organising school fetes. This instilled in him an excitement about setting up something from scratch and seeing it come alive. The school also gave him a lifelong mentor in educationist Gowri Ishwaran, who explained that all one needed to do as a school was keep students happy. “When she said ‘happy’, it wasn’t just fun or pleasure but students who were nurtured while being firmly pushed,” said Sinha. This is a learning he applied above all when involved with setting up Ashoka University. The Patna school worked on the principle that challenged minds thrived best and testimony to its beliefs lies in the long list of illustrious alumni it has since produced.

Although he had what he calls a “grade deficit” in his Class 12 results and in his first year of metallurgical engineering at IIT Kanpur, it didn’t determine or mar the course of his life. This left him far less enamoured of the “exam grades will determine your future” notion that routinely plagues Indian students and parents in current times. Meanwhile, IIT brought home how inflexible the Indian education system was, forcing him to study metallurgy, a subject he had no interest in. A short course in computer science — a subject reserved for the highest rankers at IIT (which he was not) — at the institute convinced him this was his thing and he managed to do well enough to swing a job in the field. He also acted upon his IIT professors’ advice to apply and eventually head to the US to explore the field fully.

A third aspect of his upbringing was imbibing how community-driven his parents remained even as they juggled multiple responsibilities — managing their lives, looking after elders and bringing up their children, a thread he’s seen running with the generation of Indian parents in the post-Independence era. His father headed the Harijan Sevak Sangh and his mother the Bihar Council of Women. The important lesson of giving back to society has stayed with him and shaped a lot of what he finds himself doing today.

To The US And Back

Encouraged by two of his IIT professors, who suggested both a switch in disciplines and a deeper dive into the subjects he enjoyed, Sinha found himself at the University of Pennsylvania, where he took up a couple of courses in robotics in his first semester. Armed with his PhD in robotics, he logically headed to teach at the University of Toronto to find that the rigidity and politics of academia were something he couldn’t cope with.

He then chose to apply to McKinsey as a "diversified hire" — the consultancy was looking for non-MBAs at the time — and began working on a variety of projects, many of which required him to go back to India often. In 1997, he and his wife returned for good, inspired by what was happening in the country and for a variety of personal reasons, including their ageing parents.

As a young partner at McKinsey — which itself was building its practice in India — Sinha got an opportunity to work on interesting assignments such as the turnaround of the Bokaro Steel plant. He also worked closely with Chandrababu Naidu to bring the ISB in Hyderabad to life. Prior to the ISB project, he had worked on a multimedia university in Malaysia on behalf of Mckinsey but it was the ISB experience that in some sense was seminal and a culmination of everything he’d been imbibing along the way.

Other than being involved with it literally “brick by brick”, he was also the first person to live on the campus. This was a time when he remembered his mother's words — a building is only fully ready once it’s occupied and people live in it. So immersed was he in ISB that Rajat Gupta, former managing director of McKinsey, suggested he resign from McKinsey and join ISB full time but Sinha was not ready to do that at this stage. His middle-class insecurities, he said, prevented him from taking the bold step of giving up his business career although others perhaps could see that this is what brought out the best in him.

That's when he made what he now considers his first misstep: he dabbled in the media arena, first with ABP, another McKinsey client, and then turning entrepreneurial to build 9.9, a media advisory firm for which he raised some money and had modest success.

But the stint and success of ISB unleashed an aspect of his abilities that he himself perhaps could not fully appreciate at the time — universities, colleges, and institutes started knocking on his doors, seeking his expertise to set up, turn around and design new innovative degree programmes. From around 2004 till 2018, he worked to conceptualise and kick off many higher-ed initiatives including Anant National University, the Naropa fellowship in Leh and the Vedica Scholars programme, a MBA exclusively for women in Delhi among a host of others.

But, as he worked with many institutions and observed the new animal in our midst – online education — Sinha realised two things. No matter which online higher-education site one visited, they were all clones of one another. Everyone — almost without exception — offered an abundance of courses in data sciences, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and coding; in fact, one could be forgiven for thinking that the world had been transformed into a big tech factory. Almost everyone, from global giants like Coursera, Udemy, and edX to the homegrown UpGrad and, more recently, AshokaX, was offering "the same wine in different casks."

Two, he spotted a big gap. No one was focusing on the five habits or soft skills needed to succeed at the workplace — the ability to think clearly while cutting through a clutter of complex information, problem-solving, communicating lucidly and at times with persuasion, collaborating and carrying others with you and to lead a team if required.

It was to fill this yawning gap that Sinha set up what he feels is a culmination of all his learnings through his growing years and his career and possibly his last contribution in this space — a soft skill learning company Harappa Education, which has more recently been acquired by Ronnie Screwala’s UpGrad although Sinha and his co-founder Shreyasi Singh are committed to expanding it.

ALSO READ: Can We Make Greener Air Conditioners? Cooling In The Age Of Climate Change

Learnings Along The Way

Setting up and transforming education institutions in India has led to some key insights and learnings for Sinha, the biggest of which is that high-quality institutions are built on good governance above all else. “It is how decisions are taken that determines the quality of the institution one sets up, not the course or disciplines you offer or even the teaching quality on offer. This is the single most key ingredient to build a lasting institution”, he said. However, instilling this solo ingredient is hard for many who are financing such initiatives as it means letting go, which doesn’t come easy.

A second big learning in his journey has been that education must let children just be. Educating kids to become “this or that” (read: engineer or lawyer) is superfluous in some sense today as they rarely become what was envisaged or whatever they are prepared for. Schools and even colleges need to just provide great teachers who instil a desire to know more among their students. At a college level, Sinha said, he’d like to have no majors; just teachers holding interesting lessons on subjects that spark curiosity among the students who will carve their own paths as a result.

In addition to all that he currently does and various places where he lends his time for free, he is also publishing and busy digitising Nayi Dhara, a magazine to promote Hindi literature, poetry, and short stories, launched by his father in 1950. Language he feels is a very important element of our heritage and he’s keen to preserve it as best he’s able. There’s a YouTube channel and an annual event that furthers Nayi Dhara’s mission.

Over the years, Sinha has been a professor (albeit briefly), a consultant, a dean of a highly acclaimed MBA school, and an entrepreneur with a few hats. When I asked him how one can describe him in a single word, he replies “random”, laughing although he is anything but that as I am well aware.

An hour has passed and as I listen and ponder over his thoughts on education, I begin to realise even more than I already did to what extent India has “lost this plot”. Almost no school or college today provides the kind of education Sinha speaks of as they all compete in a senseless race to produce “board exam toppers and stars”. Knowledge and learning for the sake of it sounds like an obscure, distant dream, one that this country with its ancient civilisation and teachings had once embraced and perhaps even mastered but subsequently dropped for reasons that remain a mystery to all.

Sinha was the founding dean of Indian Business School, Hyderabad, founder member of Ashoka University, and is founder of the online learning institution Harappa Education.